Atlas Magazin, Issue 332, December 2020 – Article and Photos by Mehmet İlbaysözü

The Legacy of The Ice

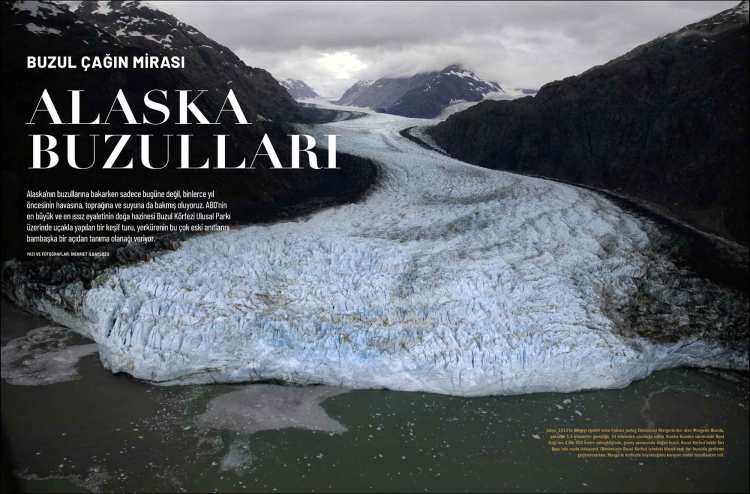

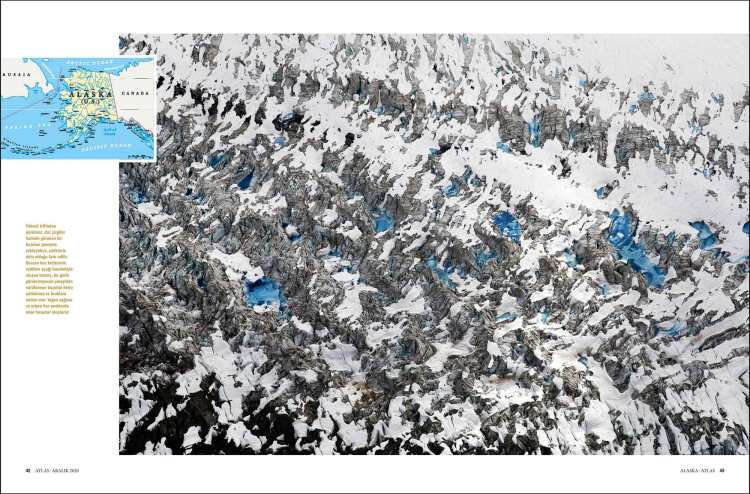

When we look at Alaska’s glaciers, we’re not just observing the present but also catching a glimpse of the air, soil, and water from thousands of years ago. A flightseeing tour over Glacier Bay National Park, the natural treasure of the United States’ largest and most remote state, offers a unique opportunity to experience these ancient monuments of the Earth from an entirely new perspective.

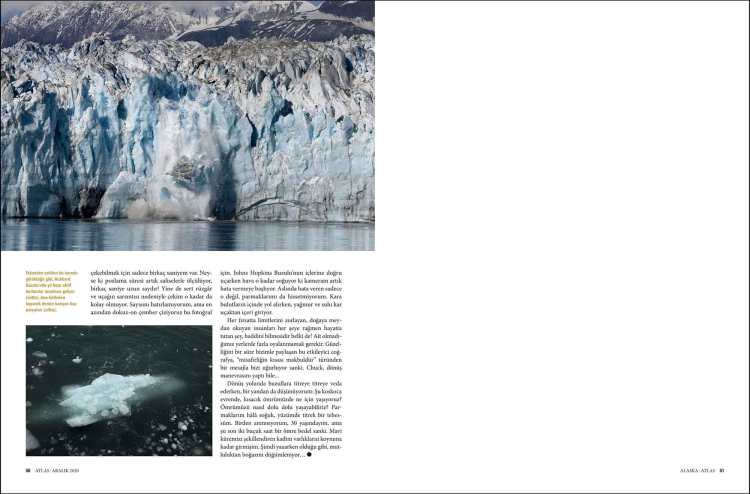

Named after the French geologist Emmanuel Margerie, who visited the region in 1913, the Margerie Glacier is approximately 1.6 kilometers wide and 34 kilometers long.

Alaska is one of the least populated regions on Earth, stretching from the northwest tip of the Americas toward Russia. With its dense forests that shelter hundreds of species, majestic mountains, and roaring rivers, this vast landscape resembles a painting. The crowning jewel of this flawless Alaskan scene is undoubtedly its glaciers. While the National Park Service officially reports 616 named glaciers in the state, it is estimated—optimistically—that the total number of glaciers may approach 100,000.

Alaska’s harsh climate softens during the summer months, opening the region to visitors. During this time, the glaciers, the area’s most popular natural wonders, can be explored from land or sea. However, to truly grasp their scale, seeing them from the air is recommended. That’s exactly what I intend to do. But most aerial tours are conducted at high altitudes with groups of 10 to 15 people. The slightly blurry photos taken from airplane windows make for pleasant summer memories in photo albums, but they’re far from satisfying for a professional photographer. For this reason, my tour operator friend Greg and I decide to charter a private plane.

Actually, the idea came to me during a short 30-minute flight over the town of Skagway, a name you might recognize from Jack London’s novel The Call of the Wild. Toward the end of the flight, the pilot, Chuck, made a kind gesture by giving me a brief tour of two nearby glaciers. After observing the Rainbow and Davidson Glaciers at low altitude near Skagway, I felt a strong desire to see and photograph Glacier Bay National Park from a bird’s-eye view as well.

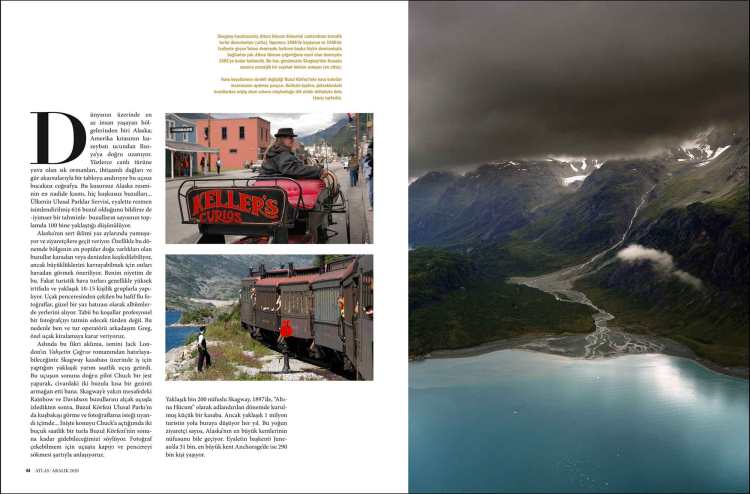

When I brought it up with Chuck upon landing, he suggested a two-and-a-half-hour tour that would take us to the far end of Glacier Bay. We agreed on the condition that he would remove the plane’s door and window during the flight to allow me to take photos. Skagway, a small town with a population of around 1,200, was established in 1897 during the era known as the ‘Gold Rush.’

Despite its small size, about 1 million tourists visit the town each year—a number that surpasses the populations of Alaska’s largest cities. For instance, the state capital, Juneau, has a population of 31,000, while the largest city, Anchorage, is home to 290,000 people.

Towards The Glacier Bay

No matter how accurate the weather forecasts are in Alaska, you always have to plan with a sense of uncertainty, as the geography and climate are deeply intertwined and can change rapidly. To avoid unpleasant surprises, we choose a day when the weather is as clear as possible. On the day of the flight, Skagway is sunny and clear, and everything seems to be going smoothly. After the plane’s door is removed for better photography, we secure ourselves and take off toward Glacier Bay.

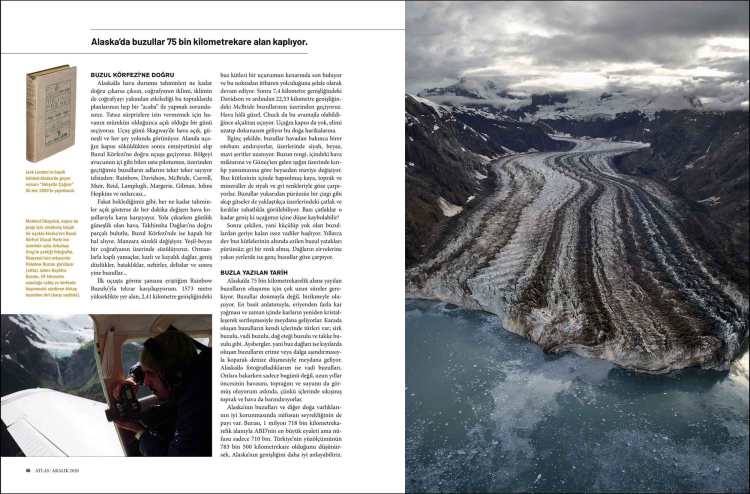

Our experienced pilot, who knows the region like the back of his hand, announces the names of the glaciers we pass over one by one via radio: Rainbow, Davidson, McBride, Carroll, Muir, Reid, Lamplugh, Margerie, Gilman, Johns Hopkins, and many more. However, as expected, despite the forecasts showing clear skies, we face rapidly changing weather conditions. The sunny skies we had at the start of our journey turn partly cloudy as we approach the Takhinsha Mountains and become overcast over Glacier Bay. The scenery is constantly changing. We glide over a green-and-white landscape—forested slopes, snow-capped and rocky mountains, vast plains, wetlands, rivers, deltas, and then more glaciers.

I once again encounter Rainbow Glacier, which I had the chance to see during my first flight. Situated at an altitude of 1,573 meters, this 2.41-kilometer-wide ice mass ends at the edge of a cliff and continues its journey as a waterfall from that point onward. Next, we pass over the 7.4-kilometer-wide Davidson Glacier and then the 22.53-kilometer-wide McBride Glacier. The weather remains favorable, and Chuck takes advantage of this by flying as low as possible. With the door removed, I feel tempted to reach out and touch these natural wonders.

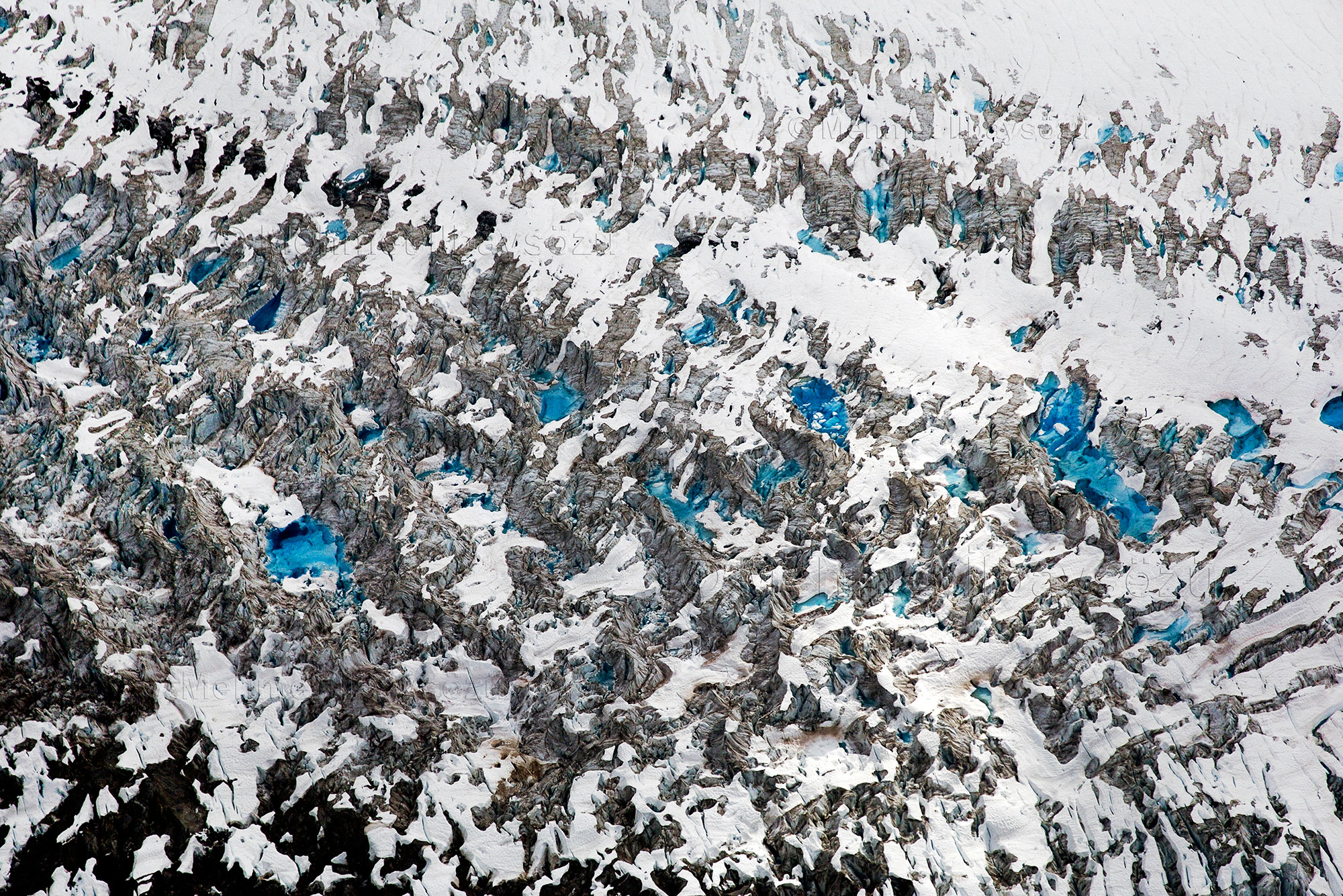

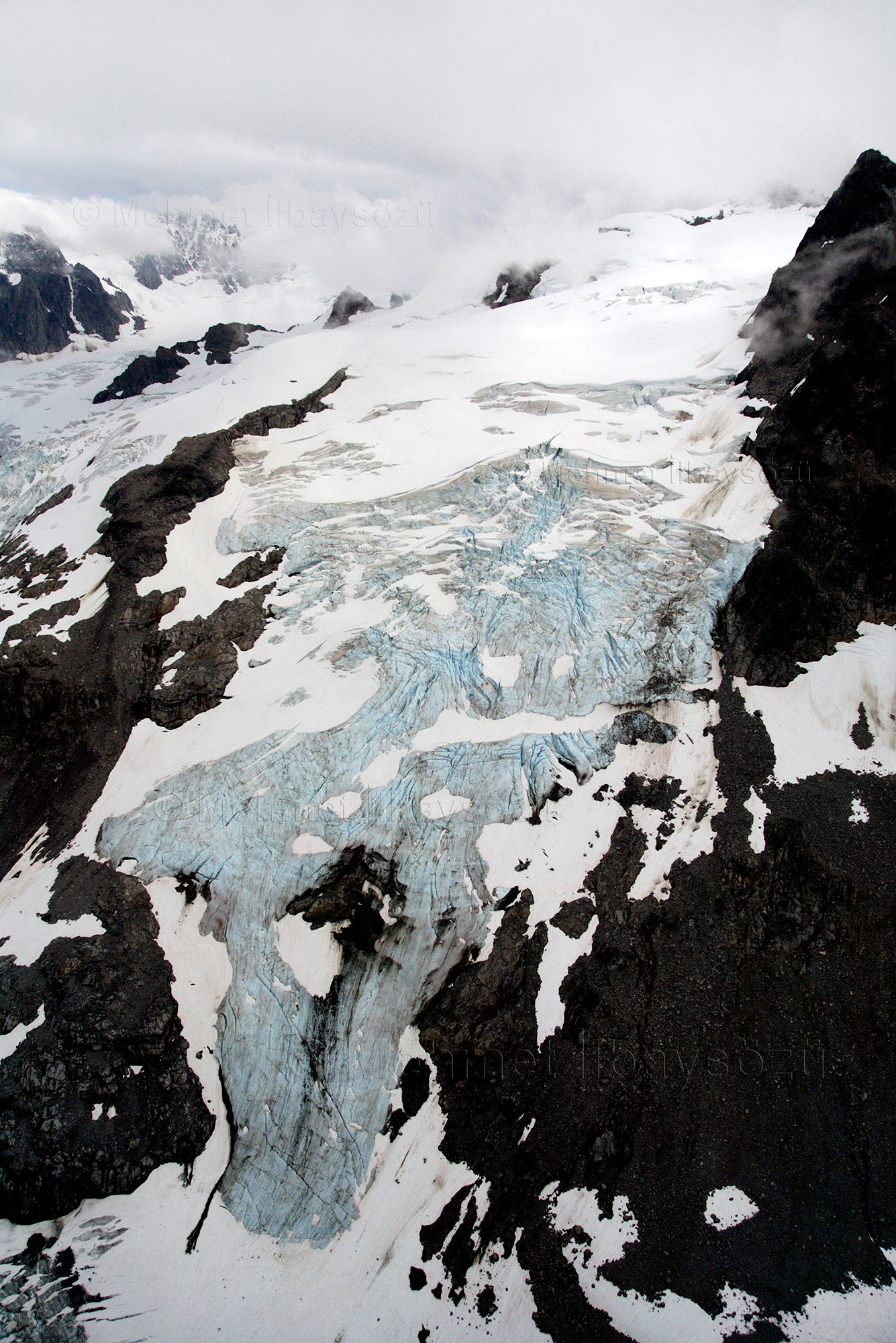

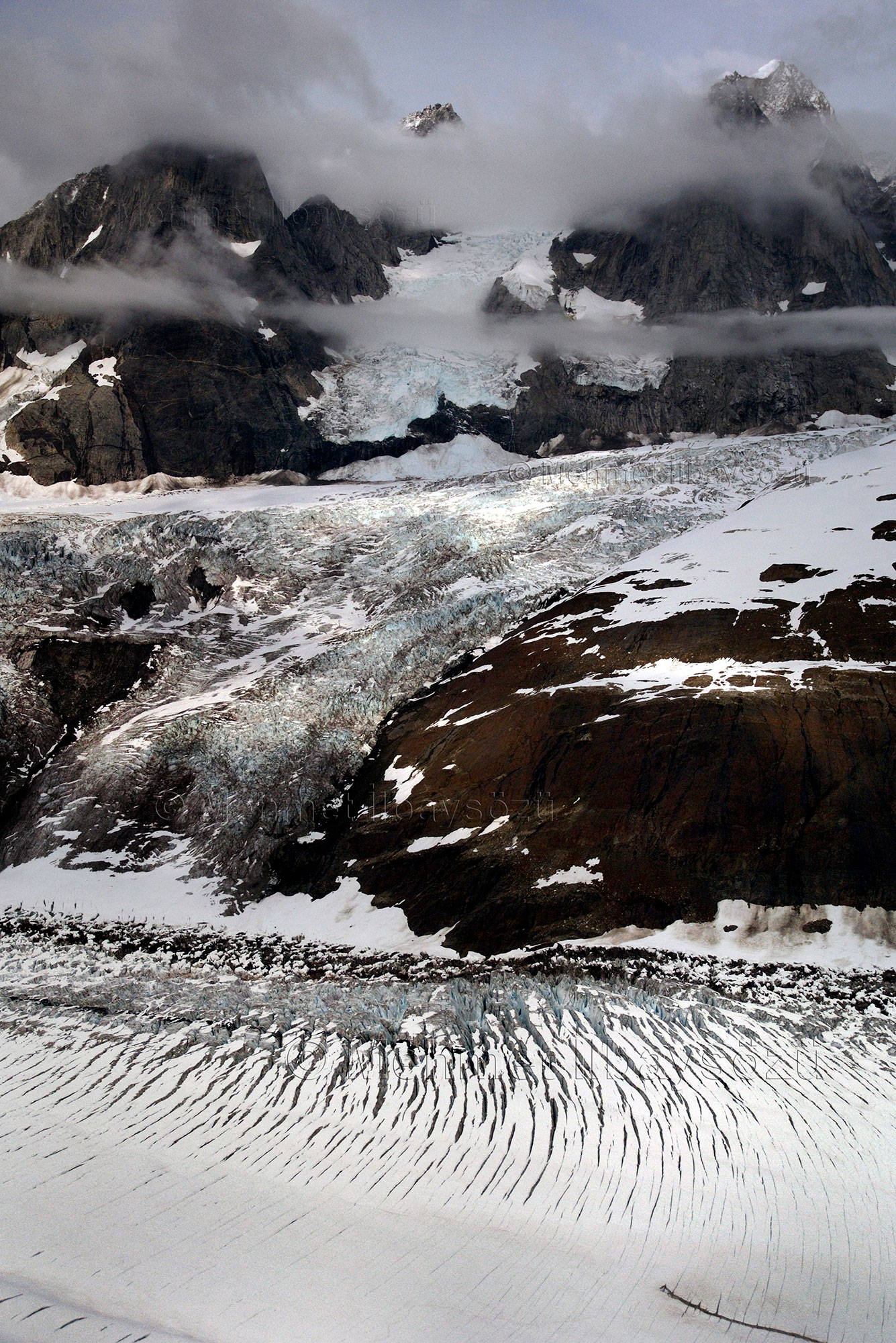

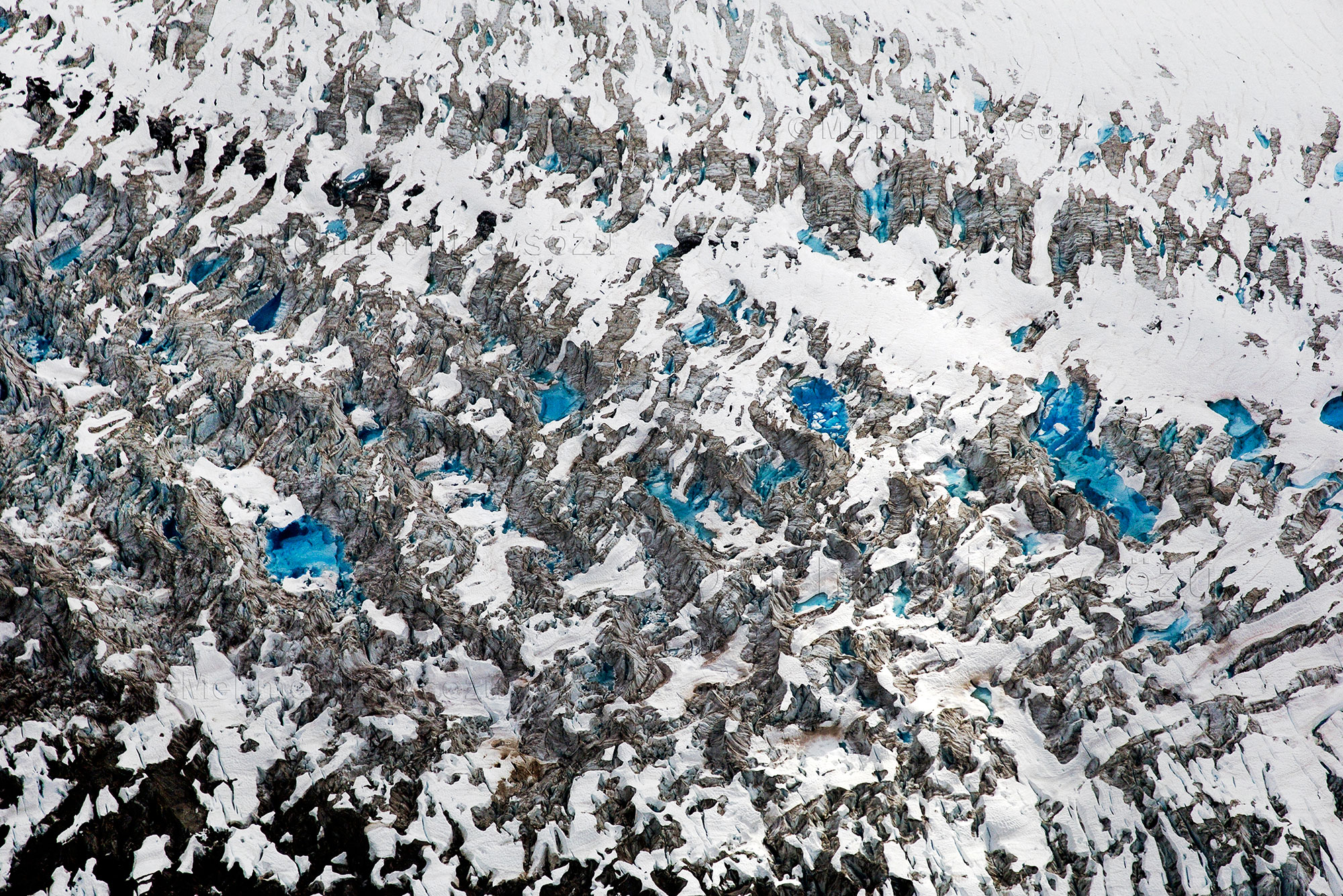

Interestingly, from above, glaciers resemble highways, with black, white, and blue streaks stretching across their surfaces. The color of the ice varies from white to blue depending on the amount of air trapped within and how sunlight refracts and reflects off it. Rocks, soil, and minerals embedded in the ice add black and gray tones to the mix. While glaciers appear smooth and seamless from above, closer inspection reveals their cracks and fissures. Some crevasses are so wide that our plane could disappear inside them if we were to fall in!

Afterward, we encounter desolate valleys left behind by receding glaciers that have shrunk or disappeared entirely. These glacial beds, compressed under massive ice sheets for centuries, are smooth and gray in color. Near the mountain peaks, young glaciers catch the eye, appearing fresh and vibrant against the rugged terrain.

History Written in Ice

The formation of Alaska’s glaciers, which span an area of 75,000 square kilometers, takes an incredibly long time. Glaciers do not form by freezing but by accumulation. Simply put, they are created when more snow falls than melts, and over time, the snow recrystallizes and hardens. Glaciers that form on land come in different types, such as cirque glaciers, valley glaciers, piedmont glaciers, and ice cap glaciers. Icebergs, on the other hand, are formed when coastal glaciers break off due to melting or wave erosion and fall into the sea. The glaciers I photographed in Alaska are valley glaciers. When I look at them, I’m not just seeing the present; I’m also glimpsing the air, soil, and water of long ago, as they hold trapped soil and air within their ice.

The sparse population of Alaska contributes to the preservation of its glaciers and other natural wonders. With an area of 1.718 million square kilometers, Alaska is the largest state in the U.S., yet its population is only 710,000. To put this into perspective, Turkey has a land area of 783,500 square kilometers. Alaska’s vastness becomes more apparent with this comparison. The state does not share a land border with the rest of the U.S. because Canada lies in between. This northern state is also a neighbor to the Russian Federation, separated by the Bering Strait. In fact, the U.S. purchased these lands from the Russian Empire in 1867 for $7.2 million. By the late 19th century, during the Gold Rush era, interest in the region grew, and new settlements were established. However, Alaska has always remained the most untouched and remote state in the U.S.

As I glide over the breathtaking scenery of Glacier Bay, a relatively small corner of this distant land, the air grows noticeably colder. Luckily, we are nearing the most beautiful glaciers. Photographing the 19.31-kilometer-wide Johns Hopkins Glacier at the far end of the bay proves to be more challenging than I anticipated. As we fly over the glacier, only the mountains surrounding the valley can be seen through the side door. But I want a full view of the glacier. When I communicate my request to the pilot via radio, he replies, “Hold tight, we’re in for a little adventure.” To capture the glacier, we need to make a tight circle between the mountain ranges on either side of the valley. The valley is so narrow, and the low-altitude flight makes the circle so small that I only have a few seconds to take the shot. Thankfully, exposure times are now measured in milliseconds, and a few seconds feels long enough! Still, the strong winds and turbulence make the task far from easy. I lose count, but we make at least nine or ten circles to get the shot.

As we fly deeper into the Johns Hopkins Glacier, the air becomes so cold that my camera begins to malfunction. It’s not just the camera—I can’t feel my fingers anymore either. As we navigate through dark clouds, rain and sleet find their way into the plane. Perhaps what keeps humans alive, despite constantly pushing limits and challenging nature, is knowing when to respect their boundaries. We shouldn’t linger too long in places where we don’t belong. This awe-inspiring landscape, which has shared its beauty with us for a while, seems to be bidding us farewell with a message akin to “short visits are best.” Chuck has already started the return maneuver.

As we shiver and say goodbye to the glaciers on our way back, I find myself reflecting: In this vast universe, during our fleeting lives, what are we living for? How can we make the most of our time? My fingers are still cold, and a faint smile plays on my face. Suddenly, I remember: I’m 30 years old, but these last two and a half hours feel like a lifetime. I’ve ventured into the embrace of the ancient entities that shaped our blue planet. Even now, as I write, my throat tightens with happiness.

Flying in Alaska

In Alaska, glacier tours are conducted by land, sea, and air. Land tours are possible for glaciers accessible by road from inhabited areas, and there must also be an observation point. Examples include tours to the Mendenhall Glacier near the capital, Juneau, and the Exit Glacier in the town of Seward. The most popular tours are by boat, while the most expensive and extreme options are plane or helicopter tours. Prices for group plane tours with 10–15 people range from $300 to $500 per person. (I paid $1,250 per hour for a private plane.) If the tour includes landing on a glacier, the costs increase even more.

Alaska’s tourism season runs from May to September, but constantly changing weather conditions must always be taken into account when planning activities in the region. It’s best to set out prepared for potential delays and cancellations.

2005-2008 © Mehmet İlbaysözü

All rights reserved. Photographs and text may not be copied, reproduced or distributed without the written permission of the owner.