Atlas Magazin, Issue 361, May 2023 – Article and Photos by Mehmet İlbaysözü

Land of The Long White Cloud

South of the world map, near Antarctica, lies a remote cluster of islands called New Zealand. In this corner of the Pacific Ocean, the geography offers all its splendor, from volcanoes to glaciers, snow-capped peaks to lush plains, pristine beaches with rich biodiversity, and high plateaus. New Zealand, with its eco-friendly lifestyle, stands as a remarkable example for the world.

NEW ZEALAND IDENTITY CARD

New Zealand consists of two main islands, the North Island and the South Island, along with more than 700 smaller islands. The two main islands are separated by the Cook Strait, which is just 22 kilometers wide at its narrowest point. The country has a population of approximately 5 million, with nearly 20% being the indigenous Māori people. The capital city is Wellington, located on the North Island, with a population of 212,000. The largest and most populous city is Auckland, also on the North Island, with 1.44 million residents. The South Island, which is larger in area, is bisected lengthwise by a mountain range known as the Southern Alps, giving it a rugged and mountainous terrain.

In contrast, the North Island is characterized by intense volcanic activity, making New Zealand a land of both volcanoes and earthquakes.

“The farthest place from where you are is the place where you already are,” I once heard someone say. And it’s not wrong. If a person keeps moving forward without changing direction, the farthest point they can reach will be the very place they started. But why, then, have I never felt so distant before? There seems to be a unique magic here, overturning all conventions. I’m in New Zealand—the southernmost, farthest, and perhaps the loneliest country on our ancient Earth.

According to British explorer Captain James Cook’s logbook, on October 15, 1769, a Māori fishing canoe approached his ship, the Endeavour. The Māori attempted to abduct Taiata, the 12-year-old nephew of Cook’s Tahitian translator and aide, Tupaia. In response, the Endeavour crew fired at the canoe, killing two Māori. Taiata managed to escape back to the ship by jumping from the canoe. Following this incident, Captain Cook named this rugged coastal area “Cape Kidnappers”.

As we journey toward the famous Australasian gannet colony near Napier, a city named after British commander Charles Napier, our guide shares this story. The colony is located about 33 kilometers from Napier, on the eastern coast of North Island, requiring a 40-minute drive to reach. I joined a tour purchased in Napier to visit the area.

In Māori, New Zealand is called “Aotearoa,” meaning “the land of the long white cloud.” According to Māori oral tradition, the semi-mythical Polynesian explorer Kupe is believed to have discovered New Zealand. Legend has it that Kupe named this land after his canoe and that a long white cloud guided him during his journey.

The first European to “discover” and document New Zealand was Dutch explorer Abel Tasman in 1642. A skilled seafarer, Tasman’s expedition ended in conflict with the Māori on the South Island, resulting in the deaths of four of his crew members and ultimately in failure. Following this incident, Europeans avoided the region for a long time. However, this initial discovery played a key role in the European colonization of Australia and New Zealand.

In 1769, the renowned British explorer, cartographer, and naval officer Captain James Cook arrived and charted nearly the entire coastline. In 1840, the Treaty of Waitangi, regarded as New Zealand’s founding document, was signed between the British Crown and Māori chiefs, making the islands a part of Great Britain.

In 1907, New Zealand became a dominion, gaining self-governance as a member of the British Commonwealth while remaining under the British Crown. The country achieved full independence in 1947, but to this day, King Charles III remains the head of state of New Zealand, which is governed as a parliamentary monarchy.

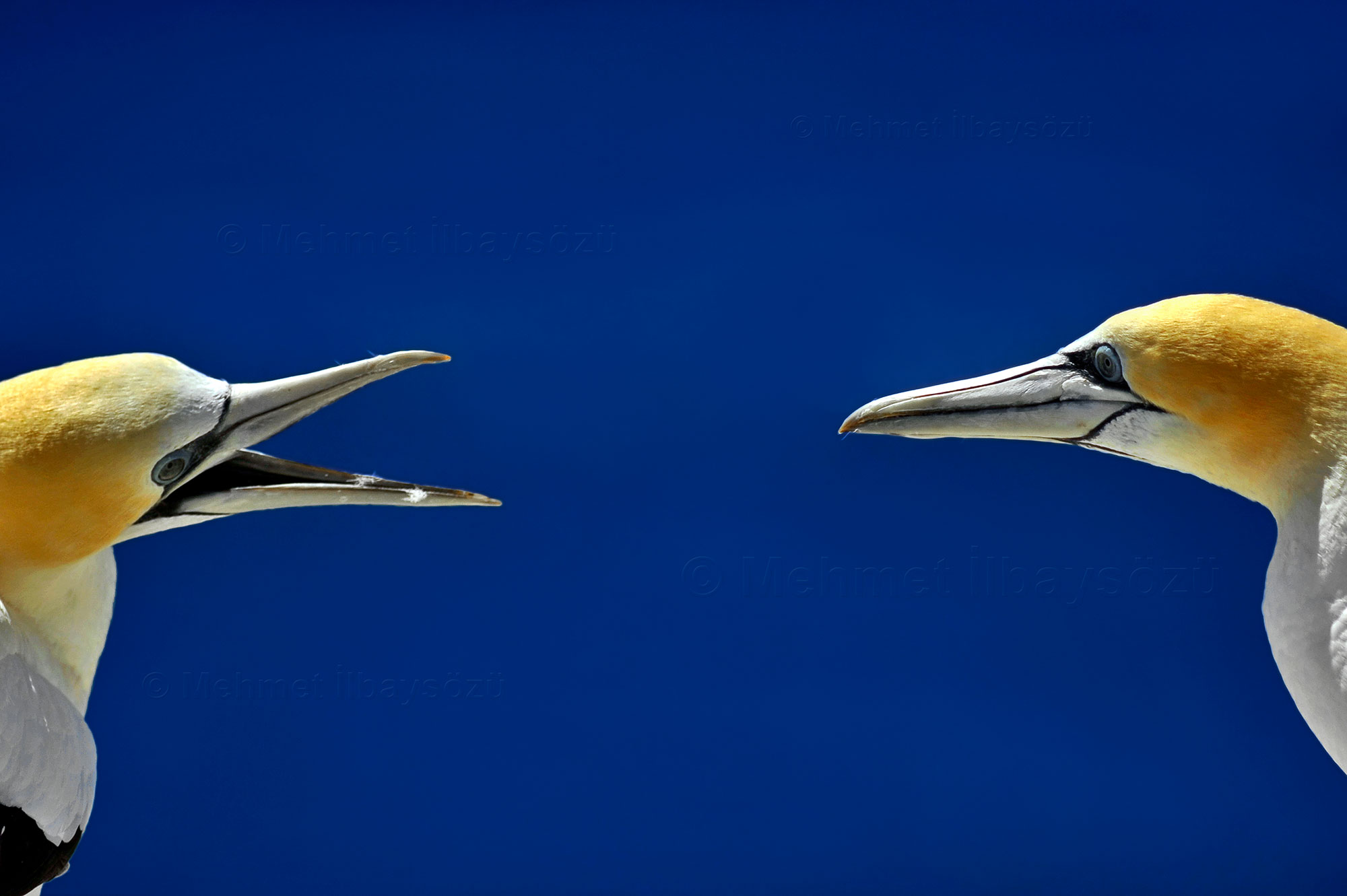

Among the Gannets

Returning to Cape Kidnappers on North Island, this famous spot witnessed the violent encounter between the Māori people and Captain Cook’s crew in 1769. Today, the area is renowned for its Australasian gannet colony. Located approximately 33 kilometers from Napier on North Island’s eastern shores, this headland is home to thousands of seabirds. Along the way, there isn’t a trace of the birds to be seen. I start to feel deceived—surely, I should at least hear the calls of thousands of these giant birds or spot a few from afar. As I ponder this, our guide seems to read my mind and jokes that they’ve tricked us and there are no birds here, laughing heartily. But then, as we crest one final small hill, the sight before me leaves me breathless.

The air is filled with a deafening cacophony, thick humidity penetrates the skin, and a sharp smell lingers. Thousands of massive gannets clash their beaks, bow their heads together, shake their heads to assert dominance in their nesting territories, or tilt their beaks skyward to signal readiness for flight. Soon enough, I grow accustomed to both the smell and the noise. These breathtaking creatures carry on with their daily routines, undisturbed by the surrounding humans. Parents tend to their chicks, while others return from foraging trips.

The chicks, covered in soft white down that makes them look like tiny dinosaurs, lack the striking colors of the adults. Juvenile birds, while having reached adult size, are distinguished by their mottled brown plumage, as their signature yellow, black, and white feathers have yet to appear. They are easily spotted, preparing for the harsh ocean conditions by practicing endless wing exercises against the wind.

Despite their hefty bodies, adult gannets are skilled hunters and divers. They can grow to 80-90 centimeters in height, with a wingspan reaching up to 180 centimeters. Gannets feed mostly in shallow waters and establish their breeding colonies in areas almost entirely surrounded by the sea—typically on islands, headlands, cliffs, and flat coastal plains. With these features, Cape Kidnappers is the perfect home for New Zealand’s largest gannet colony, h

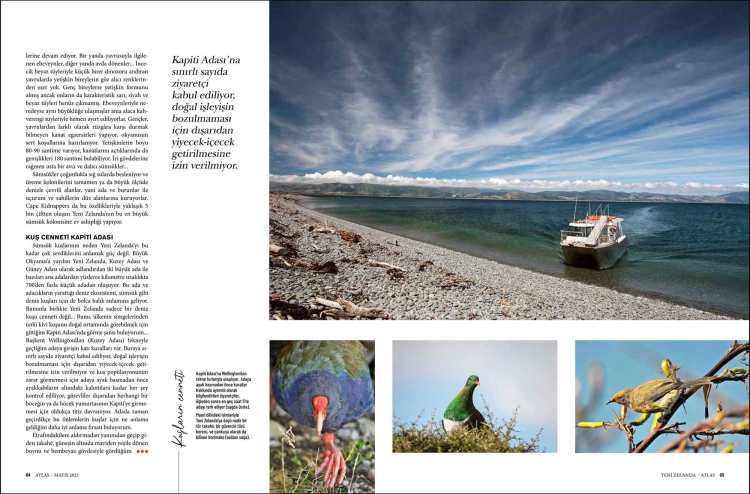

Bird Paradise: Kapiti Island

It’s not hard to see why gannets love New Zealand so much. Spanning the Pacific Ocean, New Zealand consists of two main islands, the North Island and the South Island, as well as over 700 smaller islands, some located hundreds of kilometers away from the main ones. The marine ecosystem created by these islands provides an abundance of fish for seabirds like gannets. However, New Zealand is not just a haven for seabirds. I discovered this firsthand on Kapiti Island, where I had the chance to observe the country’s iconic kiwi bird in its natural habitat.

Access to Kapiti Island is strictly regulated. Visitors can only reach the island on day trips via boat from the capital, Wellington. Entry to the island is subject to stringent rules: only a limited number of visitors are allowed, no food or drinks can be brought onto the island to preserve its natural balance, and before stepping foot on the island, even the soles of shoes are meticulously inspected to ensure no debris is carried in. Officials are extremely diligent in preventing any foreign insects or insect eggs from entering Kapiti. The more time I spent on the island, the better I understood the importance of these measures for protecting the bird population.

The island is home to an array of remarkable bird species. A takahē strolls past me nonchalantly. A kererū, one of the most beautiful pigeons I’ve ever seen, shows off its white body and neck that shimmer from blue to green under the sun. Mischievous kākā parrots try to eat everything in sight, while a weka walks right in front of me, utterly indifferent to my presence. Tiny toutouwai, smaller than the palm of my hand, flit about, while brightly colored kākāriki (whose name means “little parrot” in Māori) dart around with their green bodies and orange crests. Korimako, with its orange crown and green body, and the tūī, with its striking black body contrasted by a white tuft on its neck resembling a bow tie, are also highlights. Spotting a tūī, which is rarely seen, feels like a stroke of luck!

The birds’ apparent comfort with humans must be due to the controlled and limited number of visitors allowed on the island. Since they face fewer threats, they seem to have little need to hide. Although we had to leave the island before 5 p.m. and I didn’t get to see the nocturnal kiwi bird, I was delighted to observe so many different bird species in their natural environment.

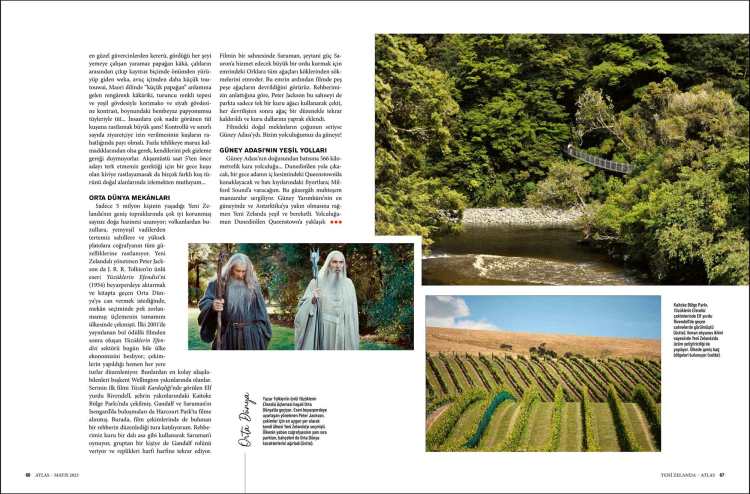

Middle-Earth Locations

In New Zealand, a country with a population of just 5 million, lies a vast expanse of well-preserved natural treasures, ranging from volcanoes to glaciers, lush valleys to pristine beaches, and high plateaus showcasing the full beauty of the geography. When New Zealand-born director Peter Jackson set out to bring J.R.R. Tolkien’s famous work The Lord of the Rings (1954) to the big screen and breathe life into the Middle-earth described in the books, he didn’t have to look far for locations. He filmed the entire trilogy in his home country.

The Lord of the Rings industry, which emerged after the award-winning first movie premiered in 2001, continues to contribute to New Zealand’s economy even today, with tours organized to almost every filming location. The most accessible ones are near the capital, Wellington. Rivendell, the Elven homeland featured in The Fellowship of the Ring, was filmed in Kaitoke Regional Park near the city. Gandalf and Saruman’s meeting at Isengard was shot in Harcourt Park.

I joined a tour led by a guide who was part of the film crew. Using a dry branch as a staff, the guide acts as Saruman, assigning someone from the group to play Gandalf and having them recite their lines word-for-word. In one iconic scene, Saruman orders his Orcs to uproot all the trees to build a massive army for the dark power Sauron. In the movie, we see tree after tree being felled. According to our guide, Peter Jackson filmed this sequence in the park using just one dry tree. After each take, the tree was lifted back into position using a mechanism, and its branches were adorned with leaves.

Most of the natural settings used in the films were located on the South Island. Our journey now takes us south!

Greenways of the South Island

A 566-kilometer road journey from the east to the west of the South Island… I’ll depart from Dunedin, spend a night in Queenstown, located in the island’s interior, and then head to the fjords on the west coast, reaching Milford Sound. This route offers breathtaking scenery. Despite being in the Southern Hemisphere’s far south and close to Antarctica, New Zealand is lush and fertile.

The first leg of my journey, from Dunedin to Queenstown, spans about 300 kilometers and takes roughly four hours. I savor the ever-changing green landscapes along the way. As we near the city, we stop at New Zealand’s largest wine cellar. Initially, no one believed it would be possible to grow grapes 45 degrees south of the equator. However, viticulture began in the Gibbston Valley in 1983, and by 1987, the first wine was released.

The owners of the facility claim that their Central Otago region is now among the world’s top three areas for Pinot Noir, alongside Burgundy in France and Oregon in the United States. The cellar, built in 1995, has a capacity for over 400 barrels. Carved into the mountain, it requires no artificial intervention for temperature and humidity control.

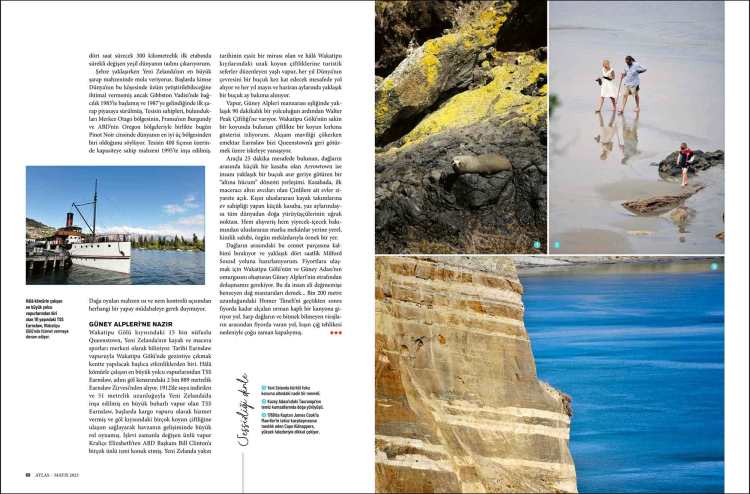

Overlooking the Southern Alps

Located on the shores of Lake Wakatipu, Queenstown is a town of 15,000 residents known as New Zealand’s hub for skiing and adventure sports. One of the top activities in the area is a cruise on Lake Wakatipu aboard the historic Earnslaw steamer. The TSS Earnslaw, one of the largest coal-powered passenger steamers still in operation, takes its name from the 2,889-meter-high Earnslaw Peak on the lake’s edge. Launched in 1912, the 51-meter-long steamer is the largest steamship ever built in New Zealand. Initially serving as a cargo vessel, it played a crucial role in the development of the region by providing access to sheep farms along the lake’s shores. Over time, its function changed, and the ship has hosted many notable figures, from Queen Elizabeth to U.S. President Bill Clinton. A unique piece of New Zealand’s modern history, the venerable Earnslaw still operates as a tourist vessel, making trips to remote sheep farms along Lake Wakatipu’s shores. Every year, it covers a distance equivalent to one and a half laps around the Earth and undergoes maintenance for about six weeks in May and June.

The steamer takes passengers on a 90-minute journey with views of the Southern Alps, arriving at Walter Peak Farm. At this tranquil lakeside farm, I watch a sheep-shearing demonstration. As evening falls, the loyal Earnslaw pulls into the dock to take us back to Queenstown.

Just a 25-minute drive away lies Arrowtown, a small village nestled in the mountains. This historic gold rush settlement takes visitors back a century and a half. Among the attractions are houses built by the first adventurous Chinese gold miners, which are open to visitors. In winter, the village hosts international ski teams, while in summer, it becomes a favorite spot for hikers from around the world. Arrowtown is a model location with unique local establishments full of character rather than international chain stores or brands.

I leave a piece of my heart in this mountain paradise and prepare for the approximately four-hour journey to Milford Sound. To reach the fjords, we must circle Lake Wakatipu and the Southern Alps, the backbone of the South Island. This means unspoiled mountain scenery that looks untouched by human hands. After passing through the 1,200-meter-long Homer Tunnel, the road winds through a forested canyon that descends to the fjord. The journey to the fjord, surrounded by rugged mountains and endless twists and turns, is often closed in winter due to avalanche risks.

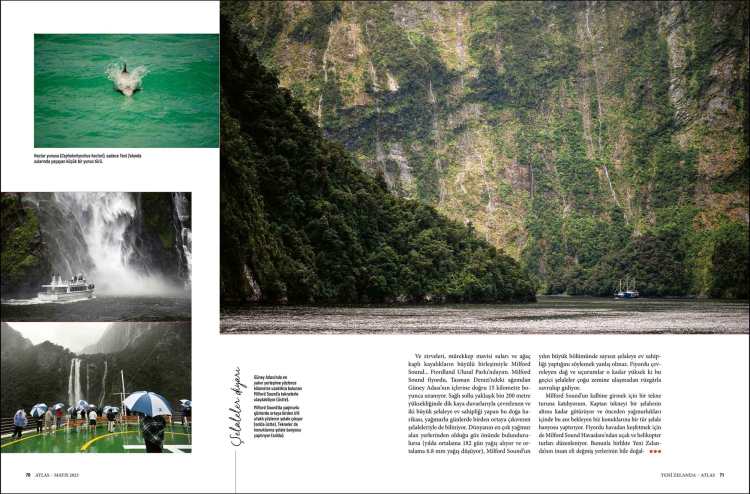

Finally, the magical Milford Sound, with its soaring peaks, inky blue waters, and forest-clad cliffs… I’ve reached Fiordland National Park. Milford Sound stretches 15 kilometers inland from its mouth at the Tasman Sea. Surrounded by sheer rock walls about 1,200 meters high, it hosts two major waterfalls and countless temporary cascades that appear after rain. Considering this area is one of the wettest places on Earth—with rain falling on an average of 182 days per year and an average annual rainfall of 6.8 meters—it’s no surprise that Milford Sound frequently features numerous waterfalls. The cliffs and mountains are so high that many of these ephemeral falls are blown away by the wind before reaching the ground.

To explore the heart of Milford Sound, I join a boat tour. The captain steers the vessel directly beneath a waterfall, offering guests, who are ready in their raincoats, a refreshing waterfall shower. For those looking to experience the fjord from above, airplane and helicopter tours operate from Milford Sound Airport.

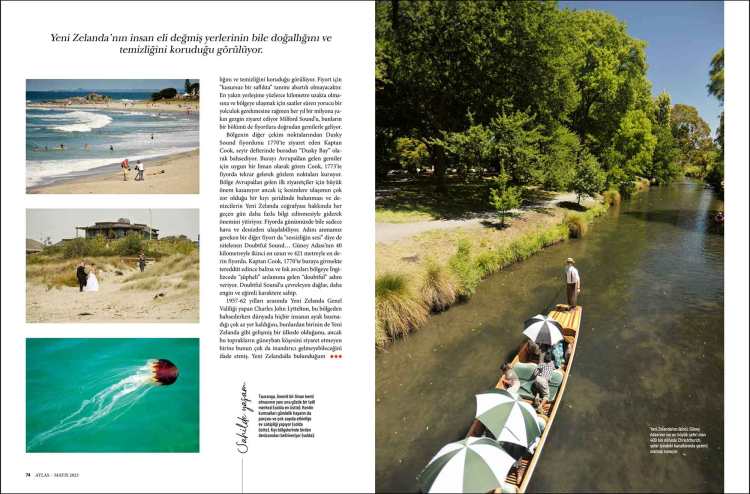

Even in areas touched by human hands, New Zealand retains its pristine beauty and cleanliness. Describing the fjord as “perfectly pure” is not an exaggeration. Despite being hundreds of kilometers from the nearest settlement and requiring hours of challenging travel to reach, Milford Sound attracts nearly one million visitors annually, with some arriving directly by cruise ships.

Another noteworthy fjord in the region is Dusky Sound, which Captain Cook visited in 1770 and referred to as “Dusky Bay” in his journal. Seeing it as a suitable harbor for ships arriving from Europe, Cook returned to the fjord in 1773 and established observation points. The region gained importance for early European visitors but gradually lost its prominence due to the difficulty of accessing the interior and the growing understanding of New Zealand’s geography. Even today, Dusky Sound is only accessible by air or sea.

Another fjord worth mentioning is Doubtful Sound, described as “the sound of silence.” At 40 kilometers, it is the second-longest fjord on the South Island and, at 421 meters, the deepest. Captain Cook hesitated to enter this fjord in 1770, prompting whalers and sealers to name it “Doubtful,” reflecting his uncertainty. The mountains surrounding Doubtful Sound are more expansive and gently sloping than those around Milford Sound.

Charles John Lyttelton, who served as New Zealand’s Governor-General from 1957 to 1962, once remarked that very few untouched places remain on Earth, and one of them exists in a developed country like New Zealand, though this might be hard to believe for anyone who hasn’t visited its southwestern corner. During my time in New Zealand, I experience what he meant every day. Despite ranking highly in terms of economic development and quality of life, New Zealand exemplifies environmental cleanliness and an eco-friendly lifestyle that could serve as a model for the world. Its remote location and low population undoubtedly play a role in this remarkable state.

Journey on the Historical Railway

Now let’s leave the fjord behind and embark on a historic train journey from Dunedin, the second-largest city on the South Island.

Waiting for its passengers at the Dunedin Railway Station, built in the early 1900s, the train in its warm yellow tones resembles a toy more than a traditional locomotive, while its carriages are designed in a contemporary style. The Taieri Gorge Railway, constructed in the 1890s to connect Dunedin with the Central Otago region during the gold rush era, was primarily used by gold miners. Today, it has been transformed into a tourist route. This railway, an impressive feat of engineering given the challenging terrain, provides access to many locations that cannot be reached by road from Dunedin. Unsurprisingly, the route rewards its passengers with stunning views.

During the approximately three-and-a-half-hour journey, I, like many other passengers, find myself constantly moving around the train. Since there’s only a brief 15-minute rest at the final stop before heading back, this trip is more about the journey itself than the destination. Passengers enjoy different views from between the carriages. From the cheerful Marian, who serves snacks and drinks on board, I learn that most of the train staff are volunteers. Marian explains that she prefers helping visitors explore her country to staying idle at home. She feels fortunate to be able to spend time in nature and socialize with people from diverse cultures.

Throughout the journey, we pass through several tunnels, including the 1,407-meter-long Caversham Tunnel. Our route also includes the Wingatui Viaduct, built in the 1880s and still the largest iron structure in New Zealand.

Towards Banks Peninsula

Christchurch, with a population of approximately 400,000, is New Zealand’s second most populous city and the largest settlement on the South Island. Officially declared a city on July 31, 1856, by royal charter, Christchurch holds the title of New Zealand’s oldest city. It is one of the few cities in the world built around a central square with four complementary squares and supported by parks in its city center—a design it shares with Philadelphia and Savannah in the United States and Adelaide in Australia. The city benefits from some of the clearest and purest water sources in the world, fed by springs flowing from the rocky foothills of the Southern Alps to the west. Historically, Christchurch served as the launching point for Antarctic expeditions. Its mild oceanic climate and vibrant city life continue to make it a popular destination, attracting hundreds of thousands of travelers each year, particularly those interested in nature tourism and outdoor sports.

On September 4, 2010, the city was struck by a 7.1-magnitude earthquake that caused no loss of life. However, the second earthquake on February 22, 2011, with a magnitude of 6.3, was recorded as one of the most devastating earthquakes to hit a city center globally. It claimed 185 lives.

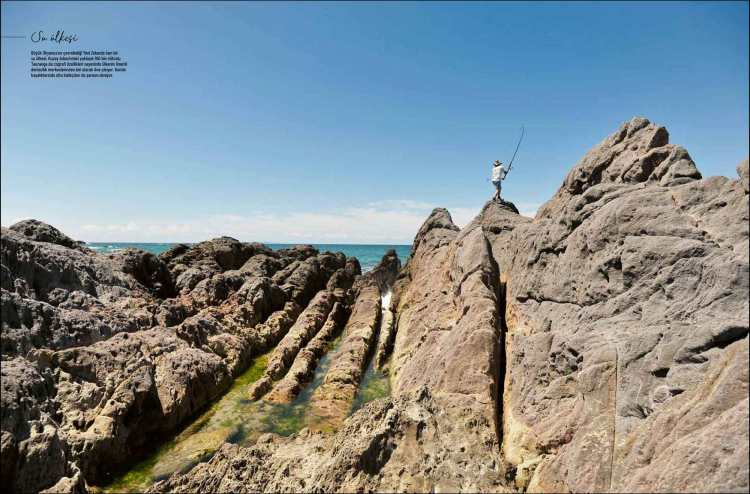

Heading southeast of Christchurch, I embark on a roughly 90-minute journey filled with natural wonders to reach Banks Peninsula. The peninsula is the most prominent volcanic area on the South Island. Captain Cook was the first to document it. On February 17, 1770, he described the peninsula as “a round shape, with a broken surface, more barren than fertile.” Mistaking it for an island due to the high landmass he observed in the background, he named it “Banks Island” in honor of Joseph Banks, the botanist aboard his ship, Endeavour. Banks Peninsula, with its many smaller peninsulas and bays, is under strict protection against net fishing. Its waters are home to a variety of marine life, including Hector’s dolphin, the smallest dolphin species, also known as the white-headed dolphin. On this trip through the peninsula’s small bays, I am lucky enough to see these beautiful creatures. I also observe numerous bird species and plenty of New Zealand fur seals basking on the rocks.

If asked about my greatest wealth in life, I would say it’s the opportunity to travel. After this long journey to New Zealand, I feel even more certain of this belief. The more one travels, the more one realizes that no possession can bring as much happiness as the beauty one witnesses. And when those beauties are in a place as remote and untouched as New Zealand, they become even more priceless for those of us from the old world. Standing on the deck of a ship, leaning against the railings and savoring the fresh ocean breeze, I find myself on the brink of another long journey. Before me lies the “Land of the Long White Cloud.” As long as we humans retain this curiosity and desire to explore, the likes of James Cook will never fade, I tell myself—perhaps arrogantly imagining myself in the shoes of the first explorers. Still, even if not for humanity, with every journey I take, I discover something new for myself and my daughter. I change, I transform.

With the hope of returning and seeing it all again one day, I take one last look at this land that has forever changed my life.

Haere rā Aotearoa, farewell New Zealand.

2008-2009 © Mehmet İlbaysözü

All rights reserved. Photographs and text may not be copied, reproduced or distributed without the written permission of the owner.