with english text – avec texte français – türkçe metinle birlikte

My Father’s Legacy

L’héritage de mon père

Babamın Mirası

Everyone assumes Paris is the capital of France, but they don’t know it’s actually an inheritance from my father.

I never knew my father. He passed away when I was just a baby. He was only 29 years old when he died. My childhood was spent listening to those around me recount memories of him.

They used to say, “Your father was a leftist.” They also said he didn’t believe in God. This was a difficult reality to accept for a conservative family like ours in the southeastern region during the 1970s. My grandmother would get very upset whenever she heard these things. “My son left this world with his faith intact,” she would say. But then they would always add something else, something I eagerly waited to hear, something that filled me with indescribable pride each time: “He was a leftist, he didn’t believe in God, but he was an incredibly honest man, very brave, afraid of nothing, and always stood firm for what he believed in. He never lied to anyone, never hurt anyone.” I don’t know what beliefs he held when he passed, but his passing left my mother and me with a very difficult life.

He was a butcher, but unlike what you’d expect from a butcher, he loved books. My mother would tell me stories: after he lost his eyesight due to his illness, he would have her read his books aloud to him. Books were considered dangerous in those days. Families would often burn them in stoves, fearing a raid might bring trouble.

As I grew older, I started to become curious about my father. I wondered if there was anything of his left behind. “There’s his wristwatch, his radio, his shaving machine, and his wedding ring,” the elders in my family would say. There was also a photo of him in an old wooden frame, wrapped in cloth, tucked away at the bottom of a chest. Whenever my grandmother wanted to cry, she would swear countless oaths to have them take it out of the chest. The old wooden frame would be retrieved ceremoniously, the cloth carefully unwrapped, and the women gathered in the room would begin their hour-long lamentation sessions.

Whenever I asked for it, they would tell me, “Not yet, grow up, get a job, get married, then we’ll give it to you.” The years passed, and one by one, my father’s mementos disappeared.

It turns out there was also a book left behind by my father, something I only discovered years later. A thick, leather-bound book with a blue cover, its pages yellowed with time: Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables. Inside the cover, it read, “Proudly Presented by Halk Publishing.” I was nine years old. The book had more than 500 pages, and not a single illustration. It was a book for grown-ups, but I had grown up quickly anyway.

I found a bookbinder in our neighborhood and had the book’s worn-out binding repaired. During this process, I became something of an apprentice to the bookbinder.

When I finished reading the book, I was no longer nine years old—I felt as though I was the same age my father had been when he died. The legacy my father left behind took me to other worlds and introduced me to other people. From that day forward, I was never the same. I constantly dreamed of Paris—and not just Paris; the entire world filled my dreams. The streets I lived on, the city I inhabited, felt too small now. I had to learn languages; I had to leave this street, this city, this country, and see other places. I had to know Paris.

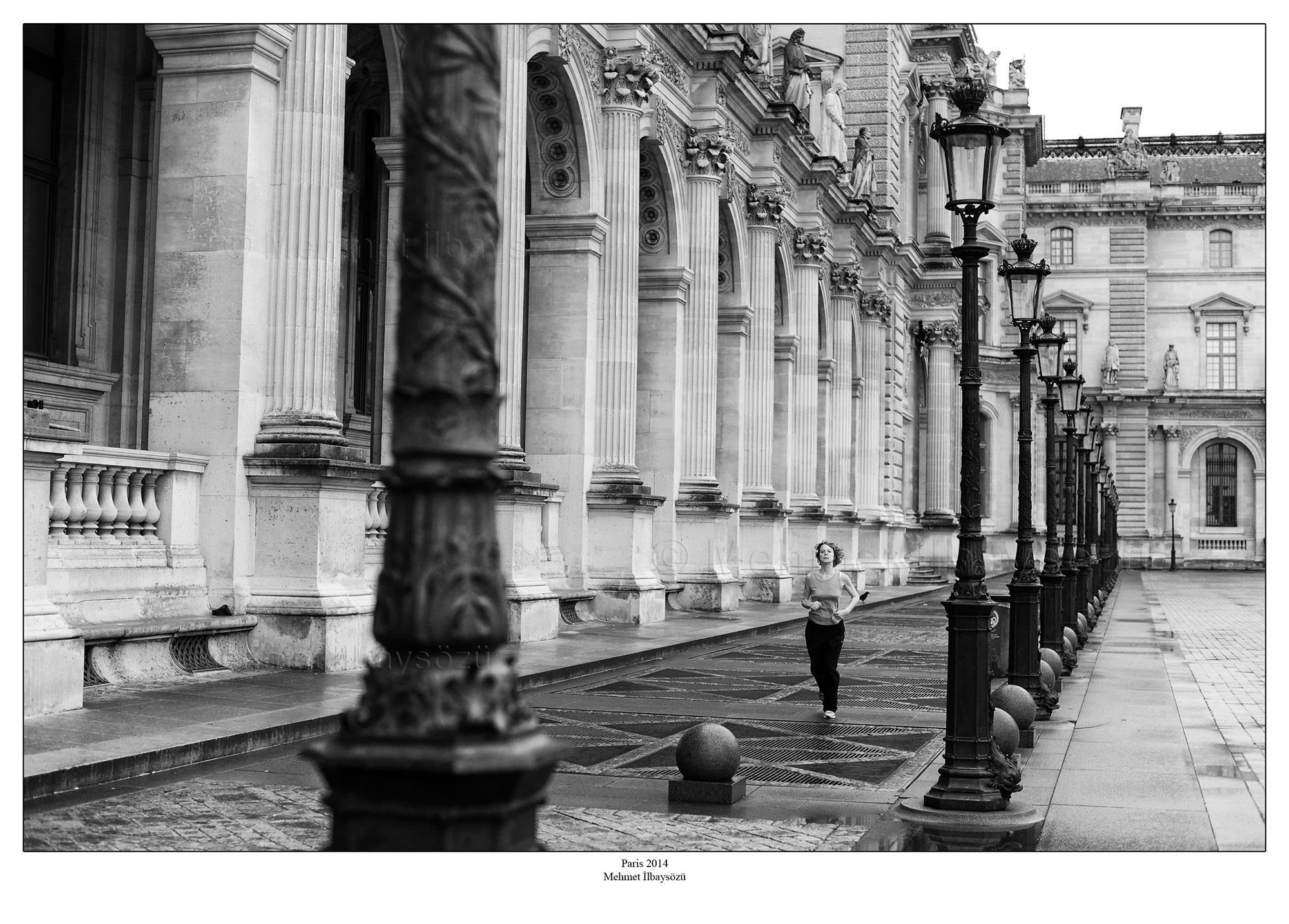

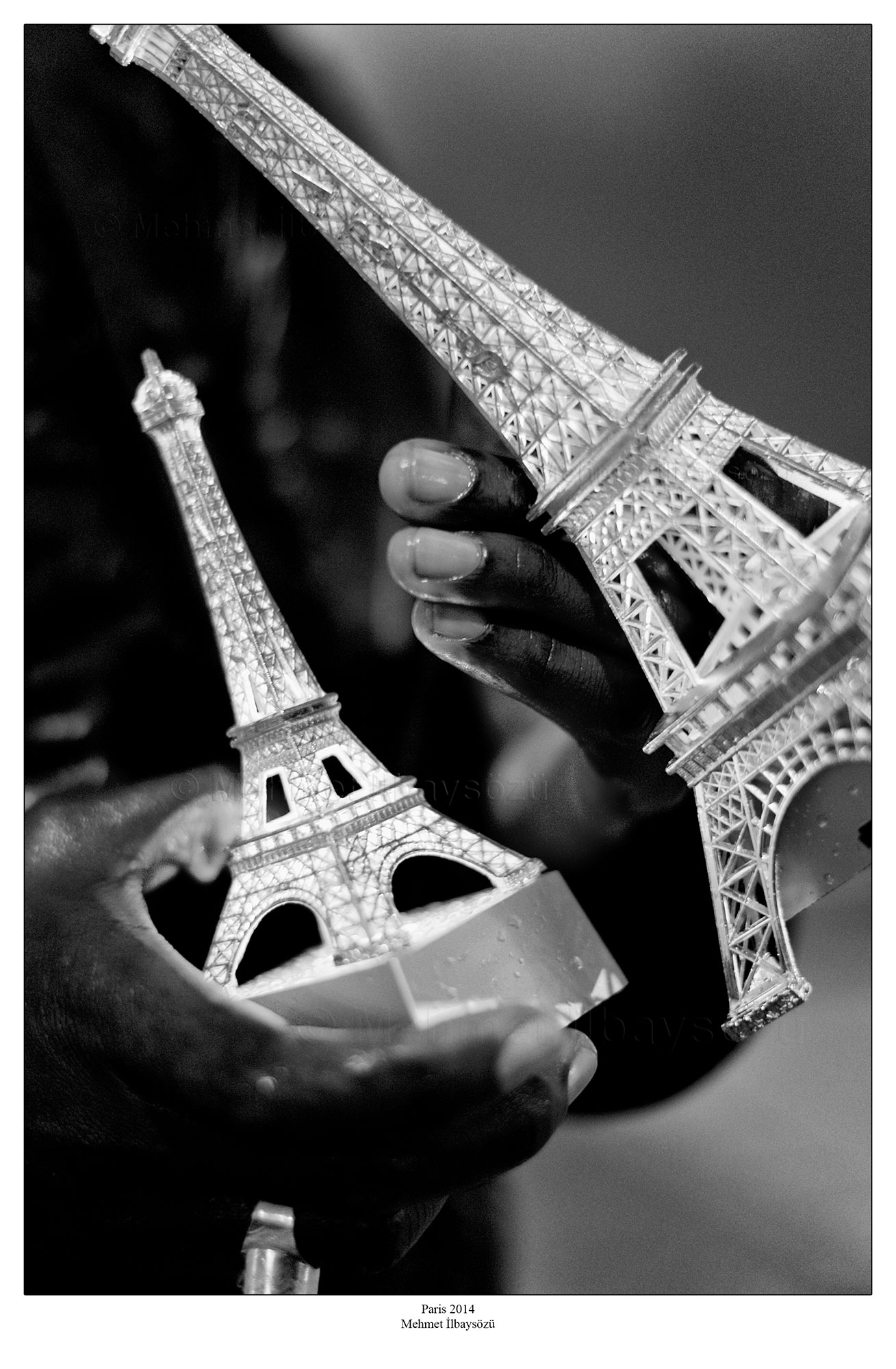

When Paris first entered my dreams, I was nine years old. By the time I visited it for the first time, I was a grown adult of thirty-three. From that day on, I returned whenever I had the chance. Everyone’s Paris is different. It’s the most touristic city in the world, loved and hated in equal measure.

People often ask me why I love Paris so much. Many people view Paris as dirty, overcrowded, and no longer the enchanting city it once was.

What they don’t know is this: every time I go there, I find that tattered, yellowed Les Misérables, the memory of my father, and, in a way, my father himself.

Because of his illness, my father never had the chance to spend time with me, but through his memories, the legacy he left me, and the single book that came into my hands, he made me who I am. He turned me into a curious traveler. I am sure that if he had lived, that butcher who questioned the world around him, who rebelled, who loved books, would have embarked on passionate, adventurous journeys, endlessly hungry to know and learn. I only understood later why I had grown up so quickly. I was, in fact, continuing from where my father had left off.

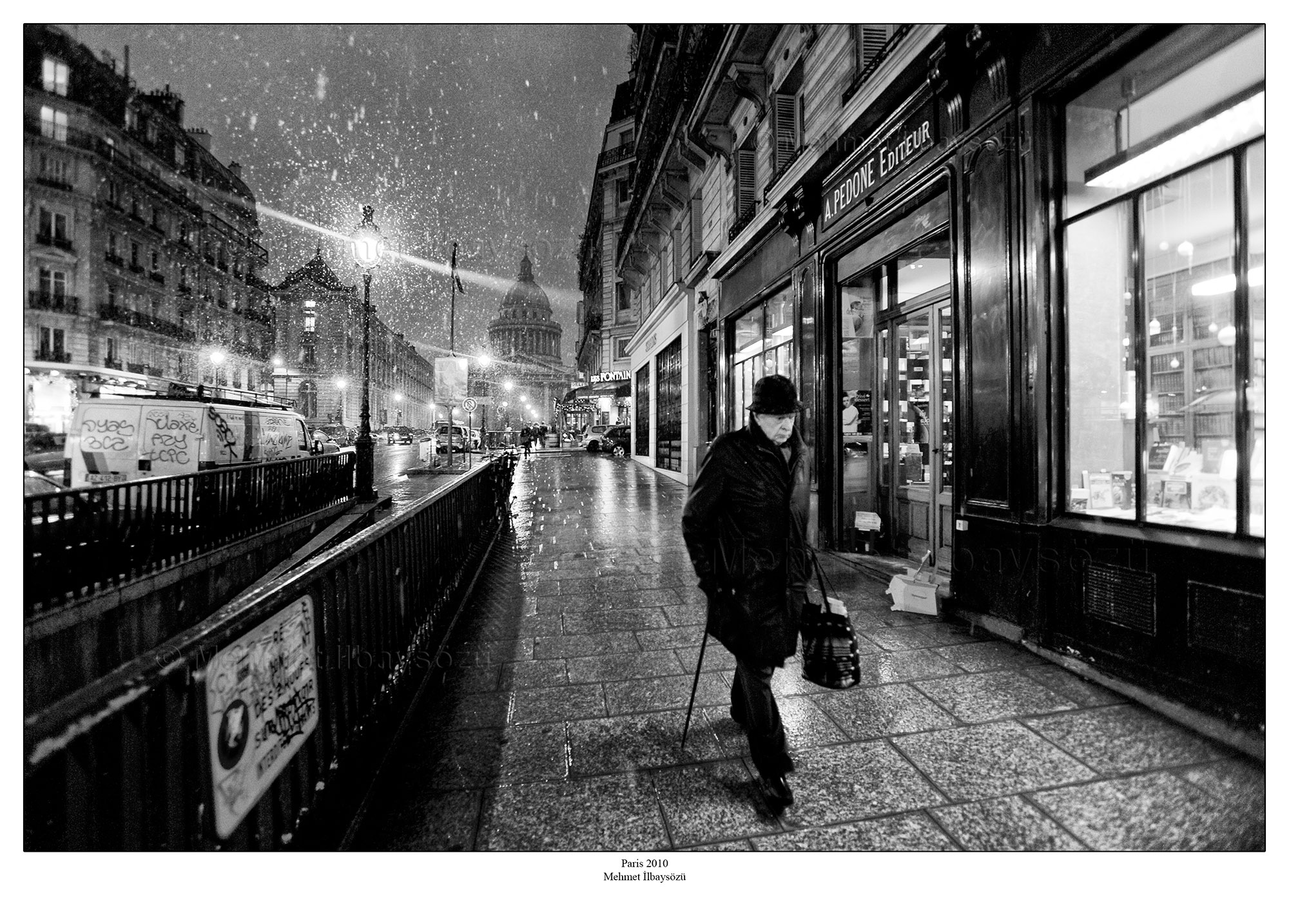

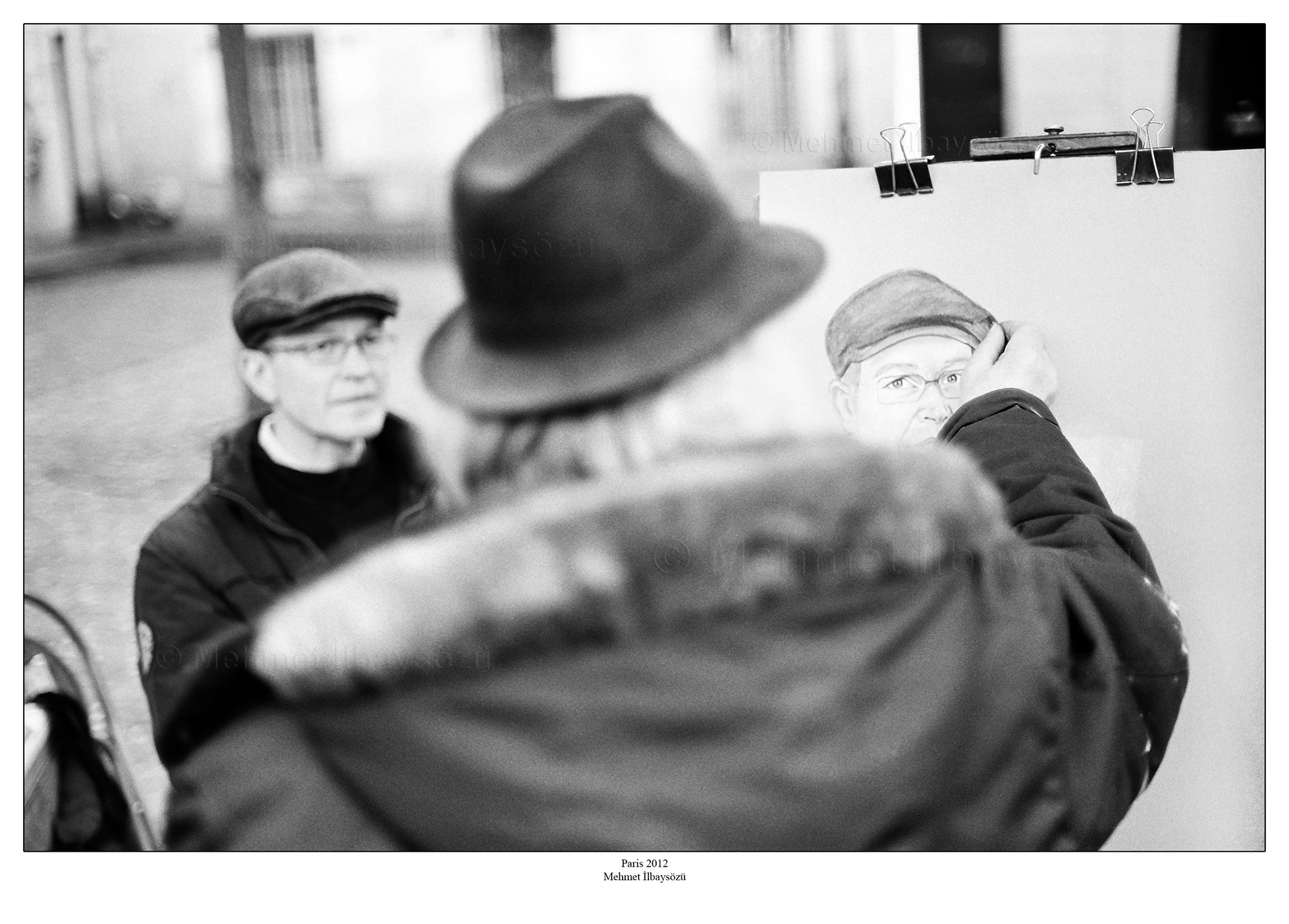

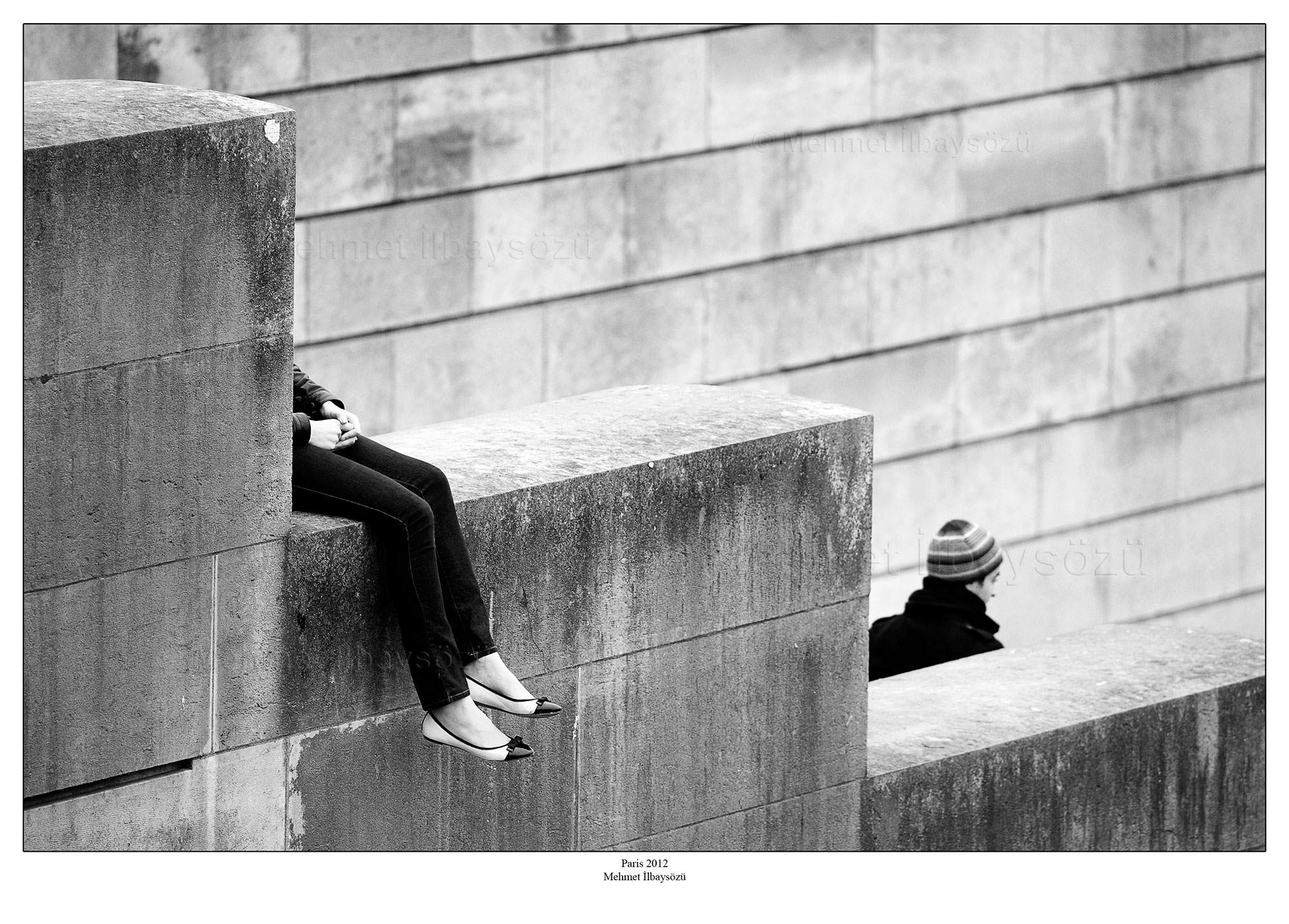

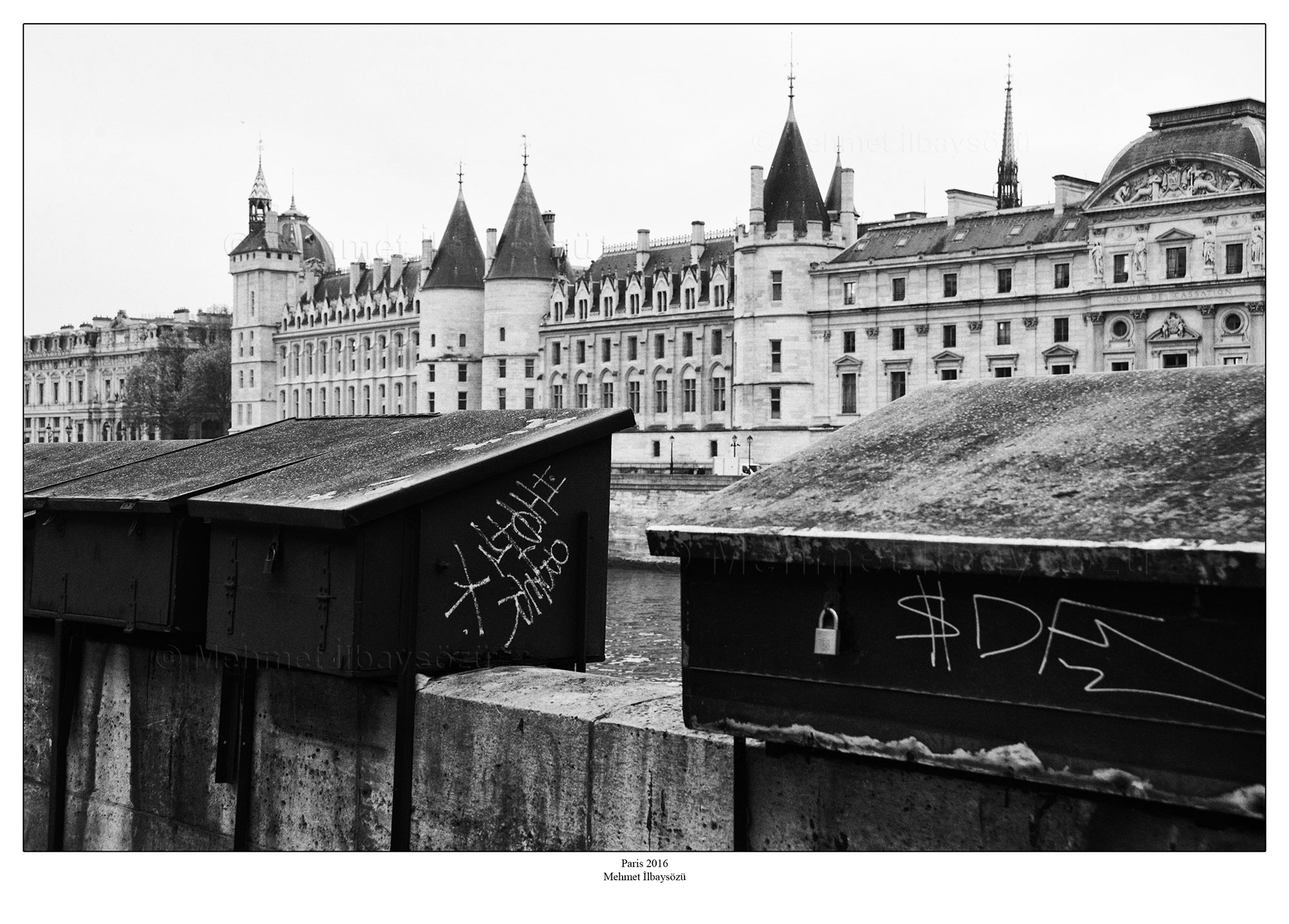

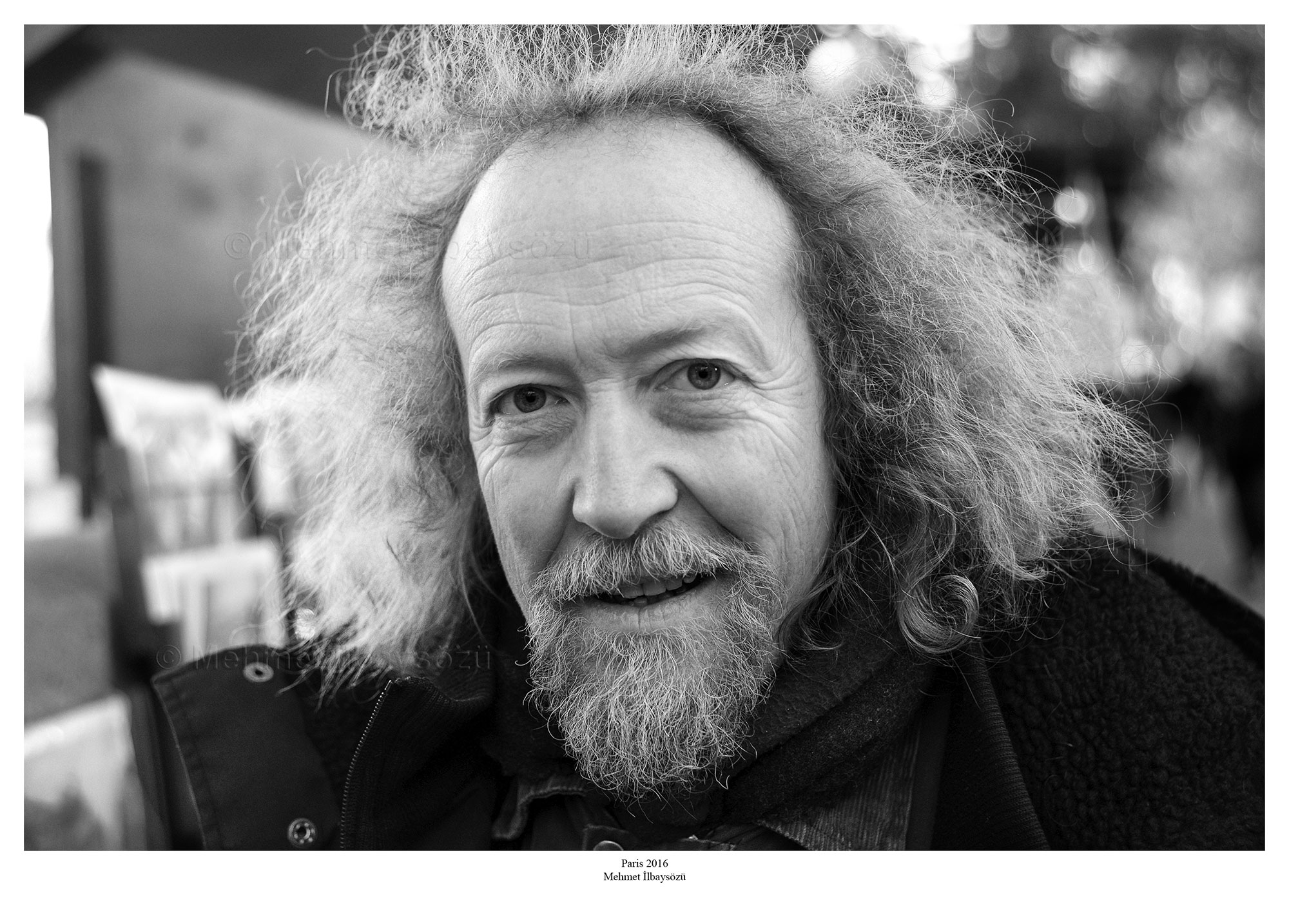

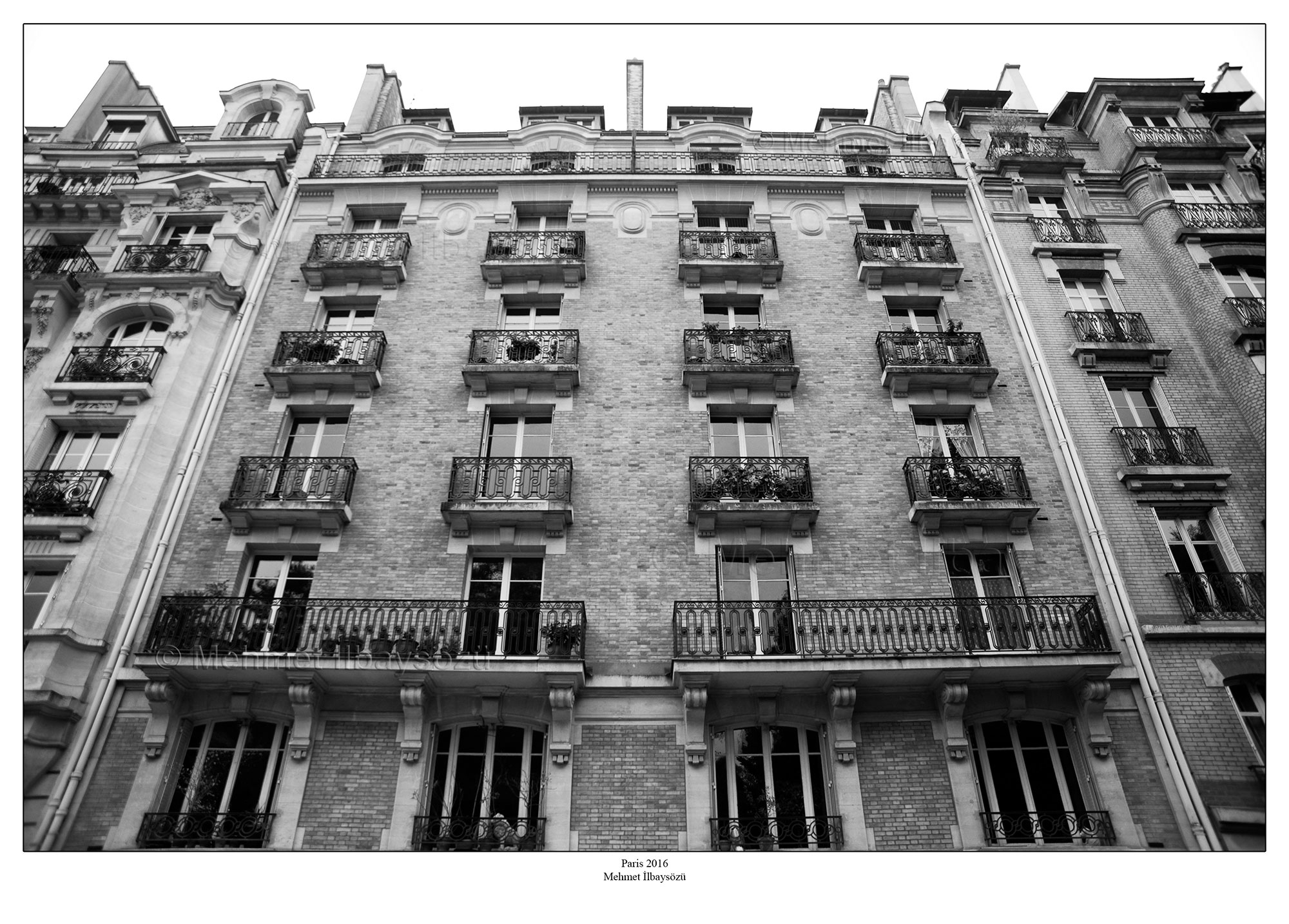

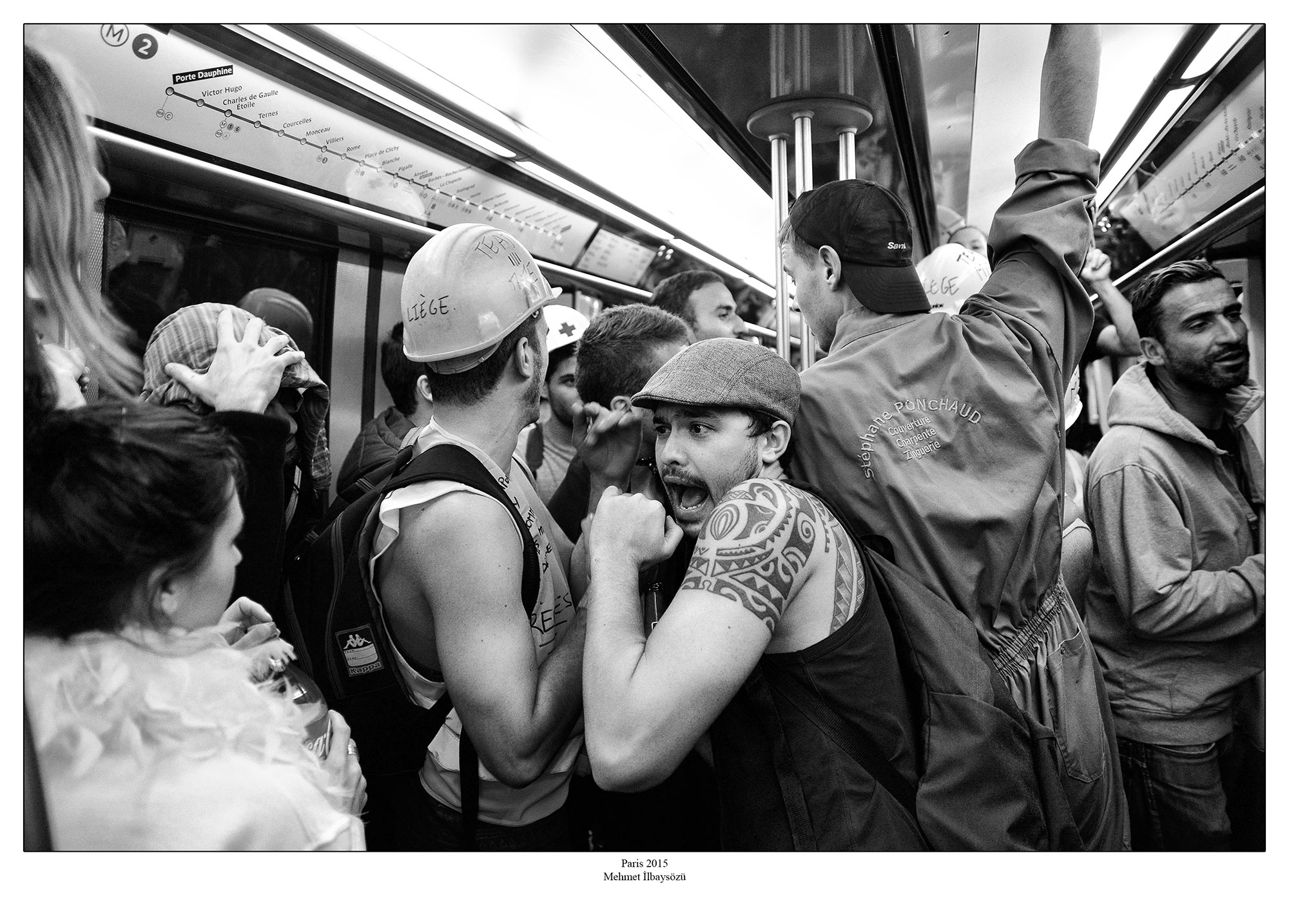

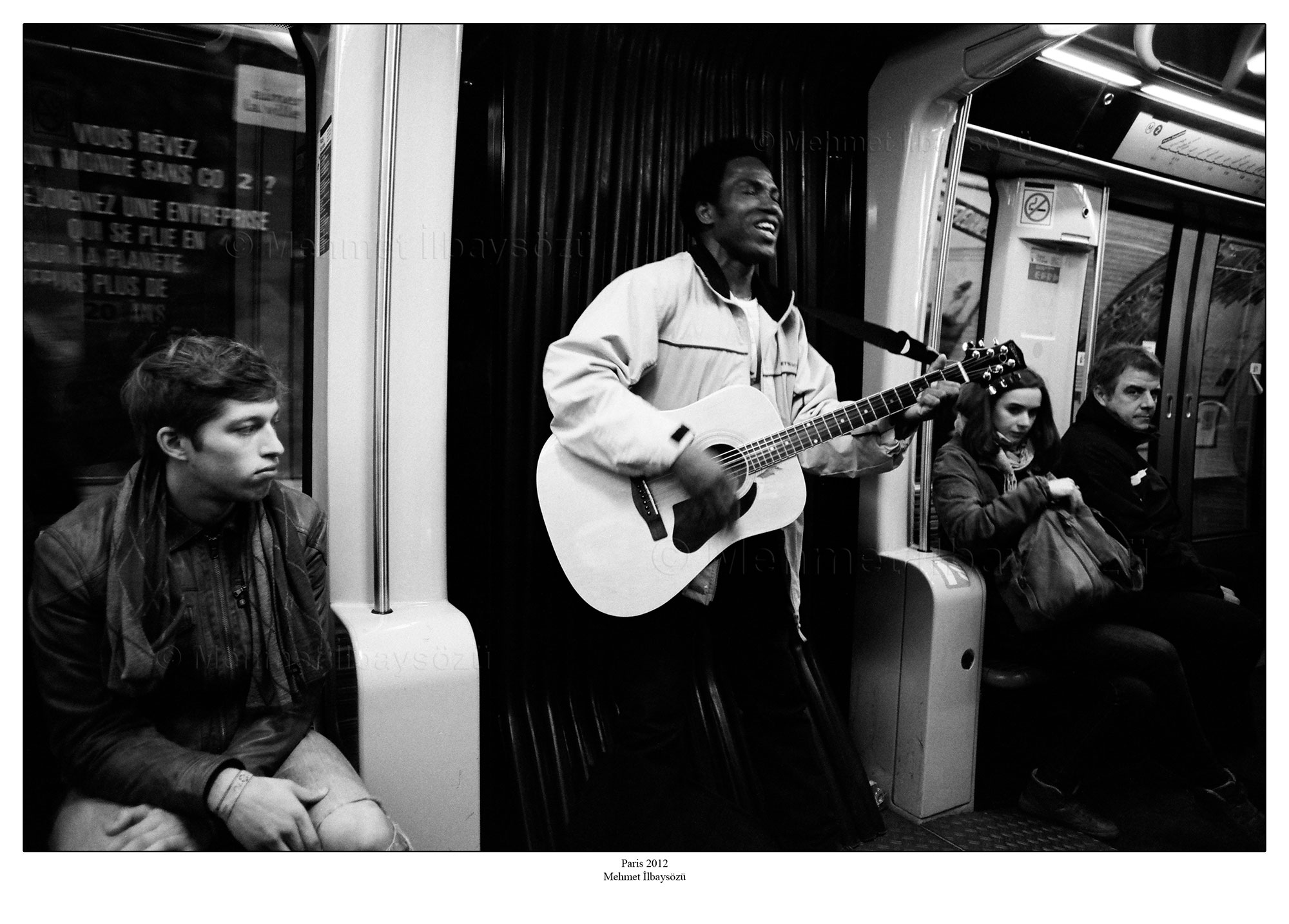

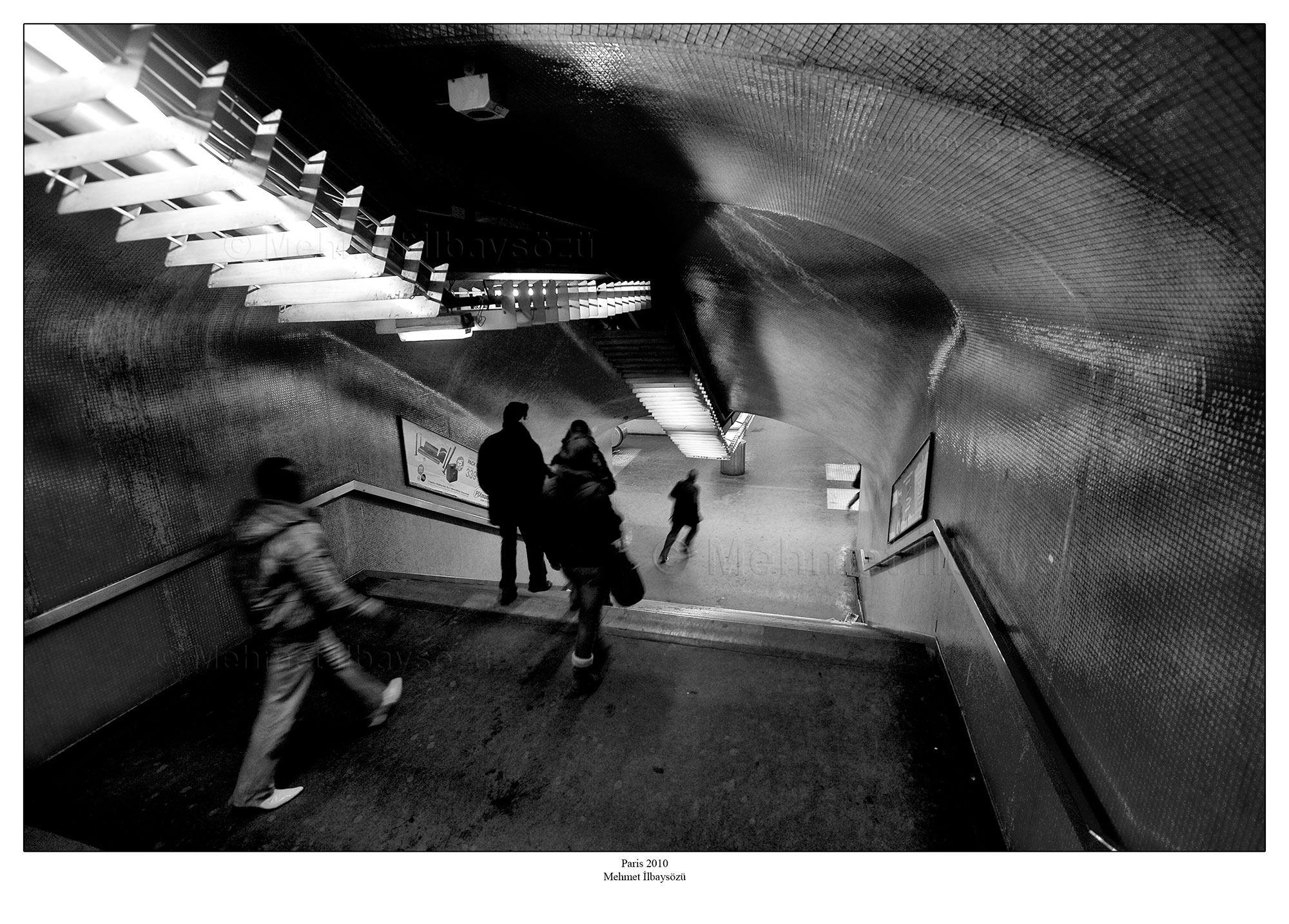

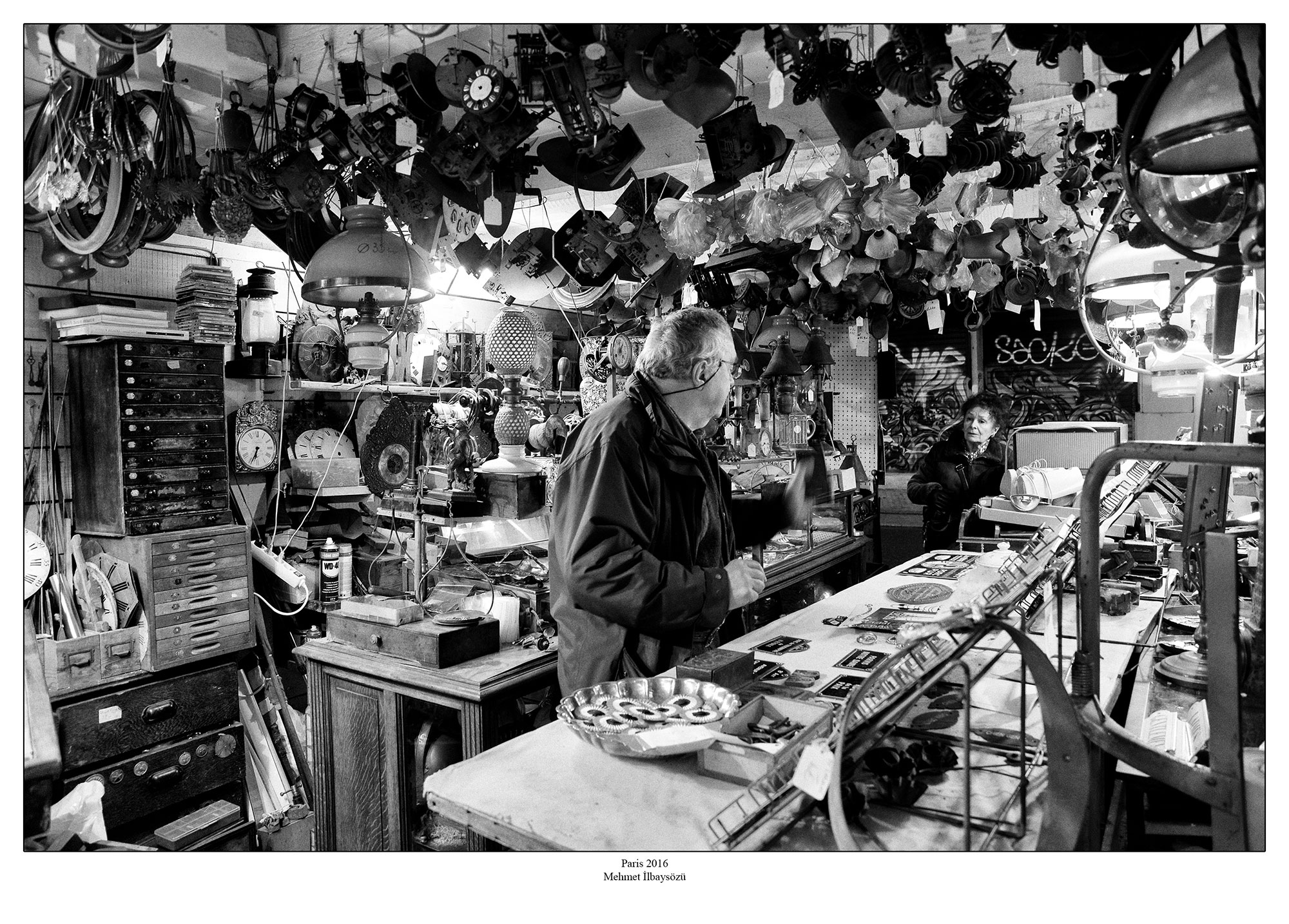

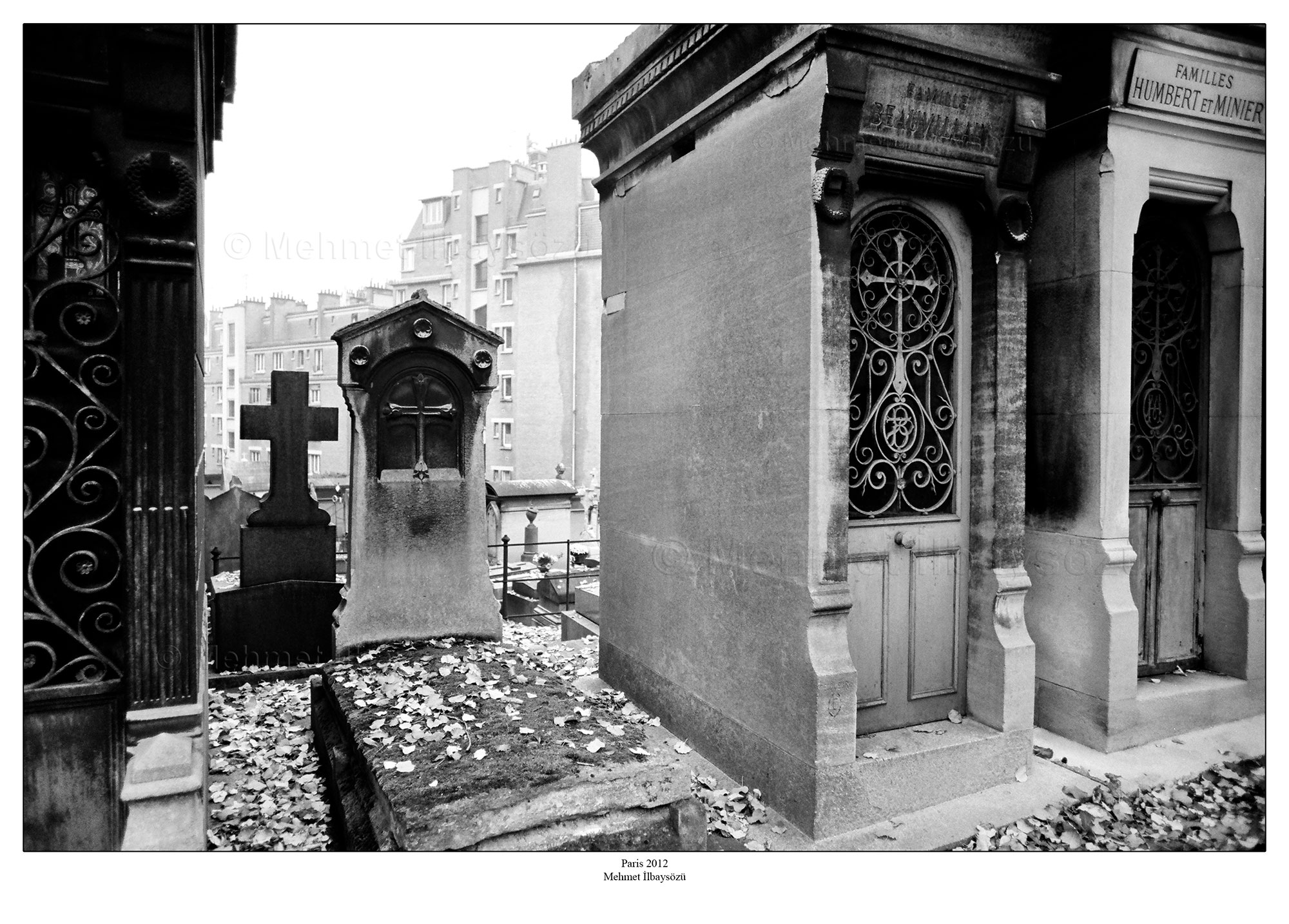

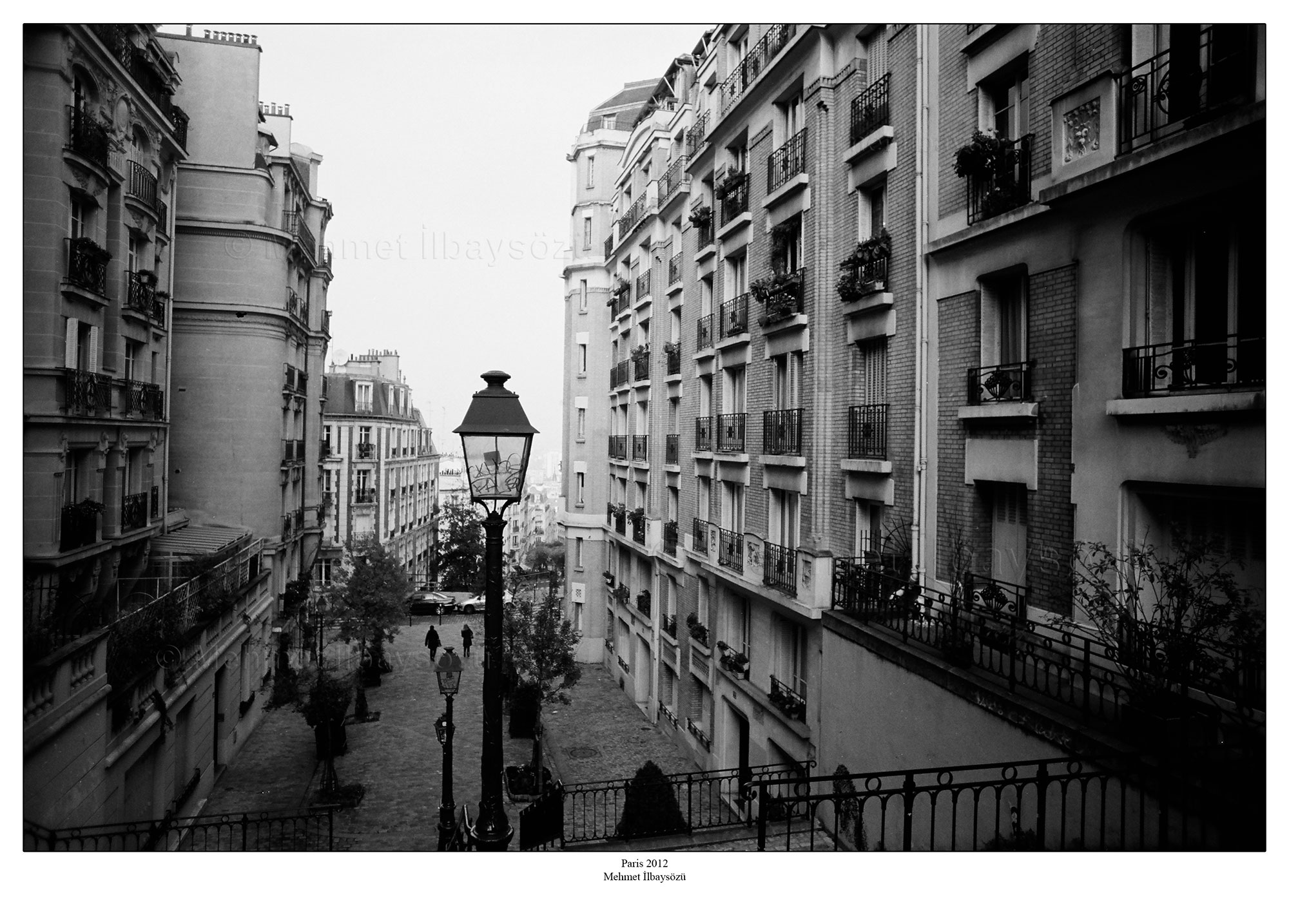

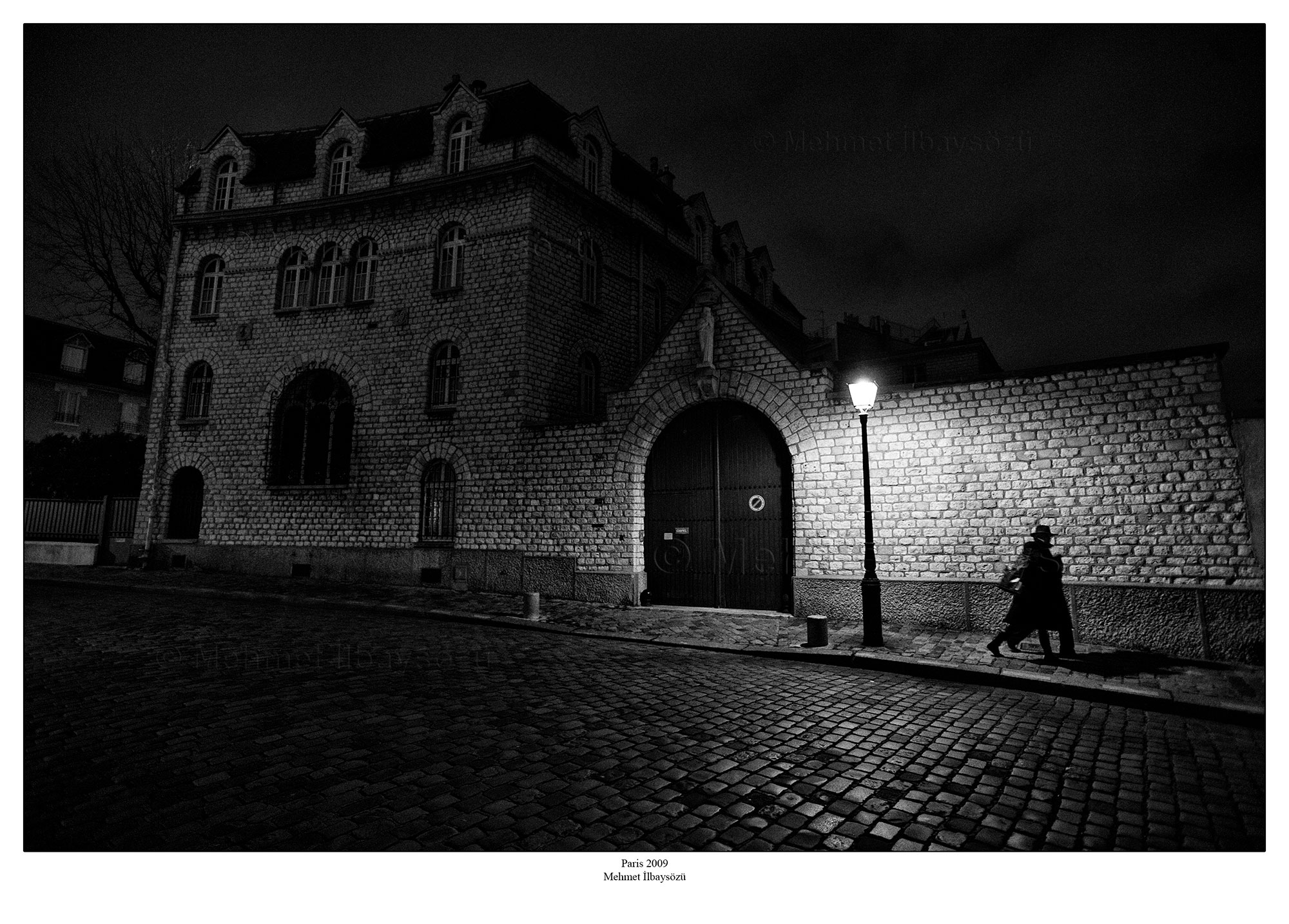

In Paris, my favorite thing to do was to walk. Now, I’m sharing with you some of the thousands of photos I’ve taken during those walks.

Here, in front of you, is my father’s legacy: Paris

Tout le monde pense que Paris est la capitale de la France, mais personne ne sait que c’est en réalité un héritage de mon père.

Je n’ai jamais connu mon père. Il est décédé quand j’étais encore un bébé. Il n’avait que 29 ans lorsqu’il est mort. Mon enfance s’est passée à écouter ceux qui m’entouraient raconter des souvenirs de lui.

On me disait souvent : « Ton père était un gauchiste. » On ajoutait aussi qu’il ne croyait pas en Dieu. C’était une réalité difficile à accepter pour une famille conservatrice comme la nôtre, dans le sud-est des années 70. Ma grand-mère se fâchait à chaque fois qu’elle entendait cela. « Mon fils est parti avec sa foi intacte », disait-elle. Mais ensuite, ils ajoutaient toujours autre chose, une chose que j’attendais avec impatience, qui me remplissait d’une fierté indescriptible à chaque fois : « Il était gauchiste, il ne croyait pas en Dieu, mais c’était un homme incroyablement honnête, très courageux, qui n’avait peur de rien et qui défendait toujours ce en quoi il croyait. Il ne mentait jamais à personne, ne faisait jamais de mal à quiconque. » Je ne sais pas quelles croyances il avait au moment de partir, mais son décès a laissé à ma mère et moi une vie très difficile.

Il était boucher, mais, contrairement à ce que l’on pourrait attendre d’un boucher, il aimait les livres. Ma mère racontait qu’après avoir perdu la vue à cause de sa maladie, il lui demandait de lui lire ses livres à voix haute. À l’époque, les livres étaient considérés comme dangereux. Les familles les brûlaient souvent dans les poêles, craignant qu’une descente de police ne leur apporte des ennuis.

En grandissant, j’ai commencé à m’interroger sur mon père. Je me demandais s’il restait quelque chose de lui. « Il y a sa montre-bracelet, sa radio, son rasoir électrique et son alliance », disaient les aînés de ma famille. Il y avait aussi une photo de lui dans un vieux cadre en bois, enveloppée dans un tissu et rangée tout au fond d’un coffre. Quand ma grand-mère voulait pleurer, elle suppliait pour qu’on la sorte du coffre. Le vieux cadre en bois était sorti comme un objet précieux, le tissu déplié délicatement, et les femmes réunies dans la pièce entamaient des lamentations qui duraient près d’une heure.

Quand je la demandais, on me répondait toujours : « Pas encore, grandis, trouve un travail, marie-toi, et là, on te la donnera. » Les années passèrent, et un à un, les souvenirs de mon père disparurent.

Il se trouve qu’il restait aussi un livre de mon père, que j’ai découvert bien plus tard. Un livre épais, relié en cuir bleu, avec des pages jaunies par le temps : Les Misérables de Victor Hugo. À l’intérieur de la couverture, on pouvait lire : « Présenté avec fierté par les Éditions Halk. » J’avais neuf ans. Le livre comptait plus de 500 pages, sans une seule illustration. C’était un livre pour adultes, mais moi, j’avais grandi vite, de toute façon.

J’ai trouvé un relieur dans notre quartier et fait réparer la reliure abîmée du livre. Pendant ce processus, je suis devenu un peu son apprenti.

Quand j’ai terminé le livre, je n’avais plus neuf ans ; je me sentais comme si j’avais l’âge qu’avait mon père quand il est mort. L’héritage qu’il m’avait laissé m’avait emmené dans d’autres mondes et m’avait permis de rencontrer d’autres personnes. Depuis ce jour, je n’ai plus jamais été le même. Je rêvais sans cesse de Paris—et pas seulement de Paris ; c’est le monde entier qui hantait mes rêves. Les rues où je vivais, la ville que j’habitais, me semblaient trop petites. Il fallait que j’apprenne des langues, que je quitte cette rue, cette ville, ce pays, pour découvrir d’autres lieux. Il fallait que je connaisse Paris.

Quand Paris est entré pour la première fois dans mes rêves, j’avais neuf ans. La première fois que je l’ai visité, j’étais un adulte de trente-trois ans. Depuis ce jour, j’y suis retourné chaque fois que j’en avais l’occasion. Chacun a son Paris. C’est la ville la plus touristique du monde, autant aimée que critiquée.

On me demande souvent pourquoi j’aime autant Paris. Beaucoup considèrent Paris comme sale, surpeuplé, et loin de la ville enchantée qu’elle était autrefois.

Ce qu’ils ignorent, c’est qu’à chaque fois que j’y vais, je retrouve ce Les Misérables abîmé et jauni, le souvenir de mon père, et, en quelque sorte, mon père lui-même.

À cause de sa maladie, mon père n’a jamais eu l’occasion de passer du temps avec moi, mais à travers ses souvenirs, l’héritage qu’il m’a laissé, et le seul livre qui est arrivé entre mes mains, il a fait de moi ce que je suis. Il a fait de moi un voyageur curieux. Je suis sûr que s’il avait vécu, ce boucher qui interrogeait le monde autour de lui, qui se rebellait, qui aimait les livres, aurait entrepris des voyages passionnés et aventureux, insatiable de savoir et de connaissance. Ce n’est que plus tard que j’ai compris pourquoi j’avais grandi si vite. En réalité, je continuais là où mon père s’était arrêté.

À Paris, ce que je préférais faire, c’était marcher. Maintenant, je partage avec vous quelques-unes des milliers de photos que j’ai prises au cours de ces promenades.

Voici, devant vous, l’héritage de mon père: Paris.

Herkes Paris’i Fransa’nın başkenti zanneder ama aslında babamdan bana kalan miras olduğunu bilmezler.

Babamı hiç tanımadım. Ben daha bebekken göçüp gitmiş bu dünyadan. Öldüğünde 29 yaşındaymış. Çocukluğum, çevremdekilerden babamın anılarını dinlemekle geçti.

Baban solcuydu derlerdi. Bir de Allah’a inanmazmış. 70’li yılların güneydoğusunda, bizimki gibi muhafazakar bir aile için kabullenilmesi zor bir durumdur bu. Nenem çok kızardı bu sözleri duyunca. Oğlum diniyle imanıyla gitti derdi. Ama bunların ardından bir şey daha söylerlerdi ki hep o anı bekler, her duyduğumda da yaşadığım gururu tarif bile edemezdim: Solcuydu, dinsizdi ama çok dürüst adamdı, çok cesurdu, hiçbir şeyden korkmaz, inandığı şeyin ardından giderdi. Kimseye yalan söylemez, kimseyi incitmezdi. Hangi inançla gittiğini bilemem ama gidişi annemle bana çok zor bir hayat bırakmıştı.

Kasapmış ama bir kasaptan beklenmeyecek derecede kitapları severmiş. Annem anlatırdı; hastalığından dolayı gözlerini kaybedince kitaplarını anneme okutur, kendisi dinlermiş. O dönem kitaplar sakıncalı görülürmüş. Aileler çoğu zaman bir baskın falan olur da başları belaya girer diye kitapları sobada yakarlarmış.

Büyüdükçe babamı merak etmeye başladım. Ondan bir parça kalmış mıydı acaba? Kol saati, radyosu, traş makinesi bir de evlilik yüzüğü var derdi aile büyüklerim. Bir de fotoğrafı vardı eski ahşap bir çerçevede, bir beze sarılı, sandığın en dibinde. Nenem ağlamak istediğinde bin yeminle sandıktan çıkarmalarını ister, eski ahşap çerçeve bir tören havasında çıkarılır, bez yavaşça açılır ve odada toplanan kadınların yaklaşık bir saat sürecek ağıt seansları başlardı.

Ne zaman istesem, “henüz zamanı değil, büyü, elin ekmek tutsun, evlen, o zaman veririz” diyorlardı. Yıllar geçti, babamın hatıraları tek tek kayboldu.

Meğer bir de kitap kalmış babamdan, yıllar sonra öğrendim. Mavi kapaklı, deri ciltli, sayfaları yıllar içinde sararmış kalın bir kitap. Victor Hugo’nun Sefilleri. “Halk Yayınevi İftiharla Sunar” yazıyordu kapağı açtığımda. Dokuz yaşımdaydım. Kitap 500 sayfadan fazla, içinde resim bile yoktu. Bu büyüklerin okuyabileceği bir kitaptı ama ben de erken büyümüştüm zaten.

Oturduğumuz mahallede hemen bir mücellit buldum, kitabın dağılan cildini yeniden ciltledik. Bu süreçte mücellitin çırağı gibiydim.

Kitabı bitirdiğimde artık dokuz değil, babamın öldüğü yaşta gibiydim. Babamdan kalan miras, beni başka diyarlara götürmüş, başka insanlar tanımama vesile olmuştu. O günden sonra hiç eski ben olamadım. Hep Paris’i düşledim; hatta sadece Paris de değil, tüm dünya rüyalarımdaydı artık. Artık yaşadığım sokak, yaşadığım şehir dar geliyordu. Diller öğrenmeliydim, bu sokaktan, bu şehirden, bu ülkeden çıkmalıydım, başka yerler tanımalıydım, Paris’i tanımalıydım.

Paris düşlerime girdiğinde dokuz yaşımdaydım, orayı ilk ziyaretimde ise artık otuz üç yaşında bir yetişkindim. O günden sonra her fırsatta gittim. Herkesin Paris’i farklıdır. Dünyanın en turistik şehridir. Seveni kadar sevmeyeni vardır.

Bana neden Paris’i bu kadar sevdiğimi sorarlar zaman zaman. Çoğuna göre Paris çok kirliymiş, çok kalabalıkmış, eski Paris değilmiş…

Bilmedikleri şu ki, ben oraya her gidişimde o cildi yırtılmış, yaprakları sararmış Sefiller’i, babamdan kalan hatırayı, babamı buluyordum.

Babam hastalığından dolayı benle hiç zaman geçirememişti ama anılarıyla, bana bıraktığı mirasıyla, elime geçen tek bir kitapla beni ben yapmış, benden meraklı bir gezgin çıkarmıştı. Eminim, eğer yaşasaydı, çevresinde olup bitene itiraz eden, başkaldıran, kitaplara düşkün o kasap, iştahlı, şehvetli yolculuklara çıkacak, bilmeye, öğrenmeye doyamayacaktı. Neden erkenden büyüdüğümü de sonradan anladım. Ben aslında babamın bıraktığı yerden devam etmiştim.

Paris’te en iyi yaptığım şey yürümekti. Şimdi sizlerle bu yürüyüşlerimde kaydettiğim binlerce kareden birkaçını burada paylaşıyorum.

Huzurlarınızda baba yadigarı: Paris.

2009-2016 © Mehmet İlbaysözü

All rights reserved. Photographs and text may not be copied, reproduced or distributed without the written permission of the owner.

Tous droits réservés. Les photographies et les textes ne peuvent être copiés, reproduits ou distribués sans l’autorisation écrite du propriétaire.

Her hakkı saklıdır. Fotoğraflar ve yazılar, eser sahibinin yazılı izni olmadan kopyalanamaz, çoğaltılamaz veya dağıtılamaz.