Everyone believes Paris to be the capital of France. What they do not know is that it is, in fact, my father’s legacy. I never knew my father. He left this world when I was still a baby. He was twenty-nine years old when he died. My childhood was shaped by fragments — by stories told by others, by memories that were not mine but slowly became so.

They would say my father was a leftist. They would say he did not believe in God. In the southeastern regions of Turkey in the 1970s, for a conservative family like ours, such things were difficult to accept. My grandmother would grow angry whenever she heard these words. “My son left this world with his faith and his belief intact,” she would insist.

With the mind of a child, I did not know whether to feel sorrow or pride. But then they would add something else — something I waited for every time, something that filled me with a pride I still struggle to put into words:

“He was a leftist, he was irreligious — but he was an honest man. A brave man. He feared nothing. He followed what he believed in. He never lied. He never hurt anyone.”

I do not know what belief he carried with him when he left this world. But his leaving carved a difficult life for my mother and me.

My father was a butcher — yet he loved books in a way no one would expect from a butcher. My mother used to tell me that when illness took his eyesight, he would ask her to read to him, and he would listen. In those days, books were considered dangerous. Families burned them in stoves, afraid of raids, afraid of trouble.

As I grew older, my curiosity for my father deepened. Had anything of him remained?

“There is his wristwatch,” the elders said. “His radio. His shaving machine. His wedding ring.”

There was also a photograph. A wooden frame wrapped in cloth, hidden at the very bottom of an old chest.

Whenever my grandmother needed to cry, despite the objections of the other women, she would insist — with endless oaths — that it be taken out. The lock of the chest would be opened. The frame would emerge with ceremonial gravity. The cloth would slowly unfold. And my father’s black-and-white face — already yellowing with time, his gaze heavy with sorrow — would join us. Then the women would begin their lament, a ritual that lasted nearly an hour.

Whenever I asked for my father’s belongings, they would say: “It is not time yet. Grow up. Let your hands earn bread. Get married. Then we will give them to you.”

Years passed. I grew up. And my father’s belongings disappeared, one by one.

Only later did I learn that there had been one more thing left behind. A book.

A thick book with a blue cover, leather-bound, its pages yellowed by years. Les Misérables by Victor Hugo. Inside, the words read: Proudly Presented by Halk Publishing House.

I was nine years old. The book had more than five hundred pages. There were no pictures. It was a book meant for adults — but I had already grown up early.

I found a bookbinder in my neighborhood. We rebound the book together. In the process, I became his apprentice.

When I finished reading it, I was no longer nine. I felt as old as my father had been when he died.

What my father left me — his legacy — carried me into other worlds, introduced me to people I had never known. From that day on, I was never the same.

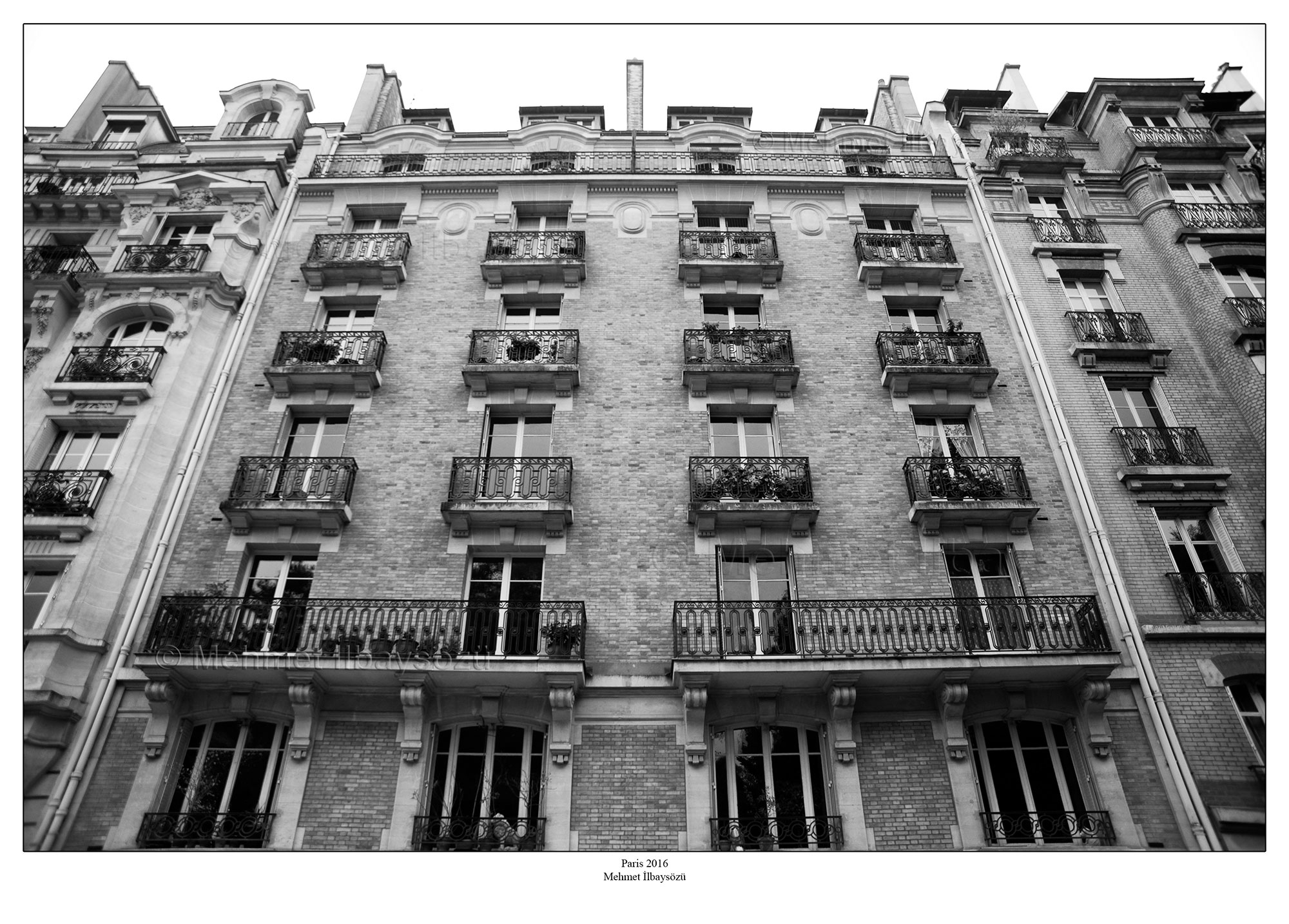

I dreamed of Paris. Not only Paris — the whole world entered my dreams. The street I lived on felt narrow. The city felt small. I had to learn languages. I had to leave. I had to see other places. I had to know Paris.

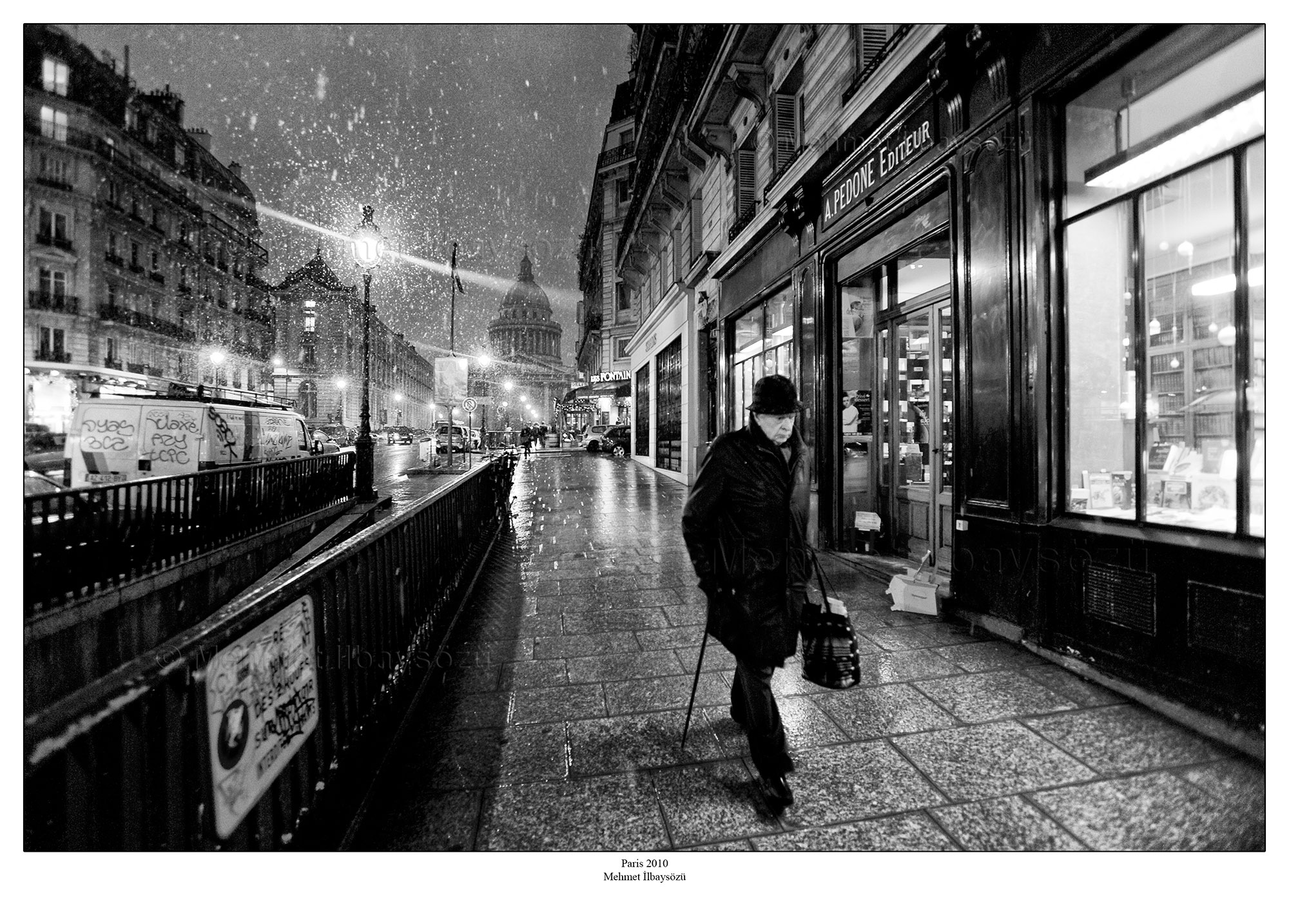

Paris entered my dreams when I was nine. I first set foot there when I was thirty-three. After that, I returned whenever I could.

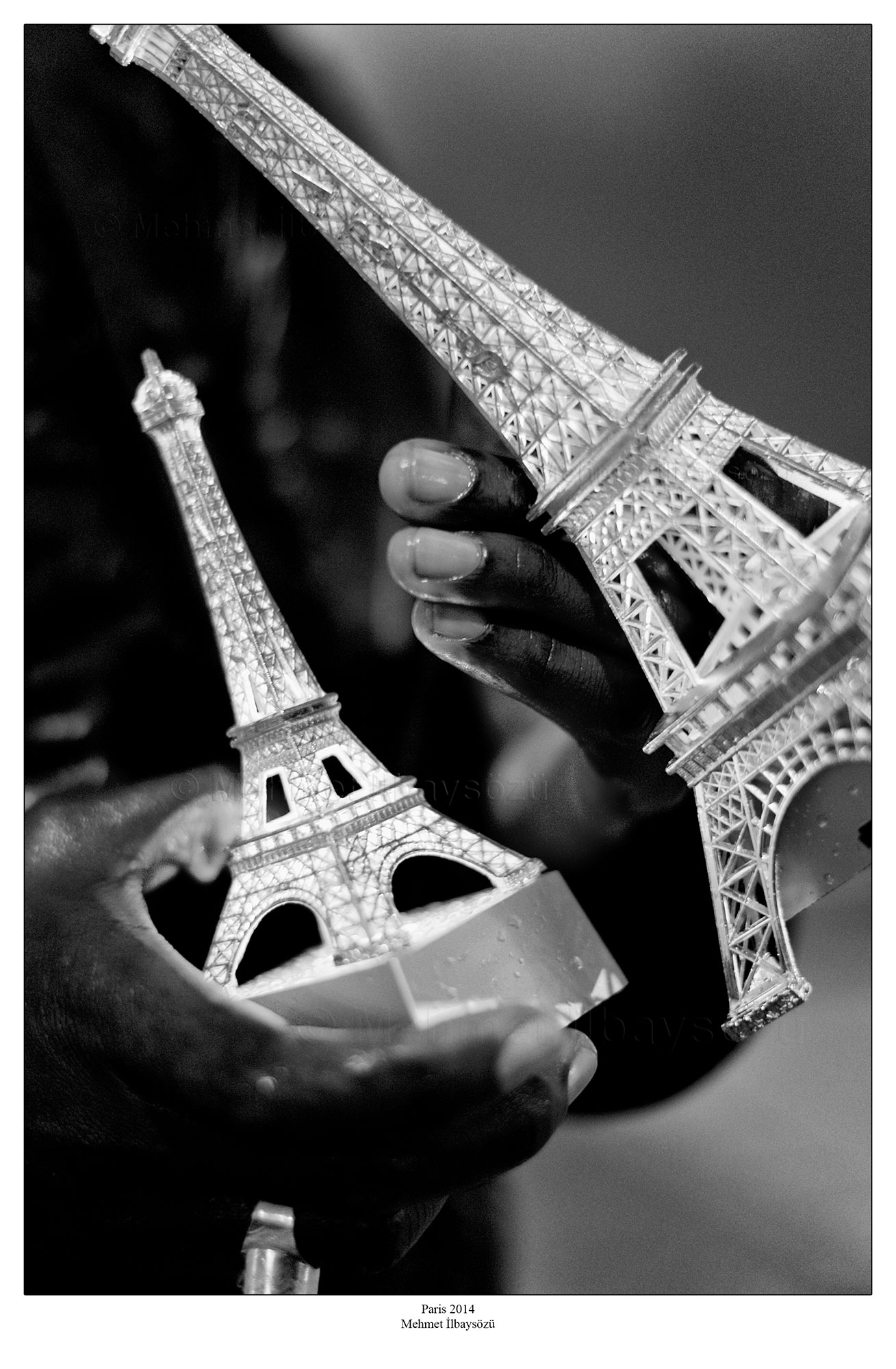

Everyone has their own Paris. It is the most touristic city in the world. It is loved as much as it is disliked.

People sometimes ask me why I love Paris so deeply. They say it is dirty. Too crowded. No longer the Paris it once was.

What they do not know is this: every time I go, I find that torn, yellowed copy of Les Misérables. I find my father. I find his legacy.

My father could never spend time with me because of his illness. Yet through his memories, through what he left behind, through a single book, he shaped who I became. He turned me into a curious traveler.

I am certain that if he had lived, that book-loving butcher — the man who objected, who resisted, who questioned — would have set out on passionate journeys, endlessly hungry to know and to learn.

Only later did I understand why I matured so quickly. I had continued from where my father had left off.

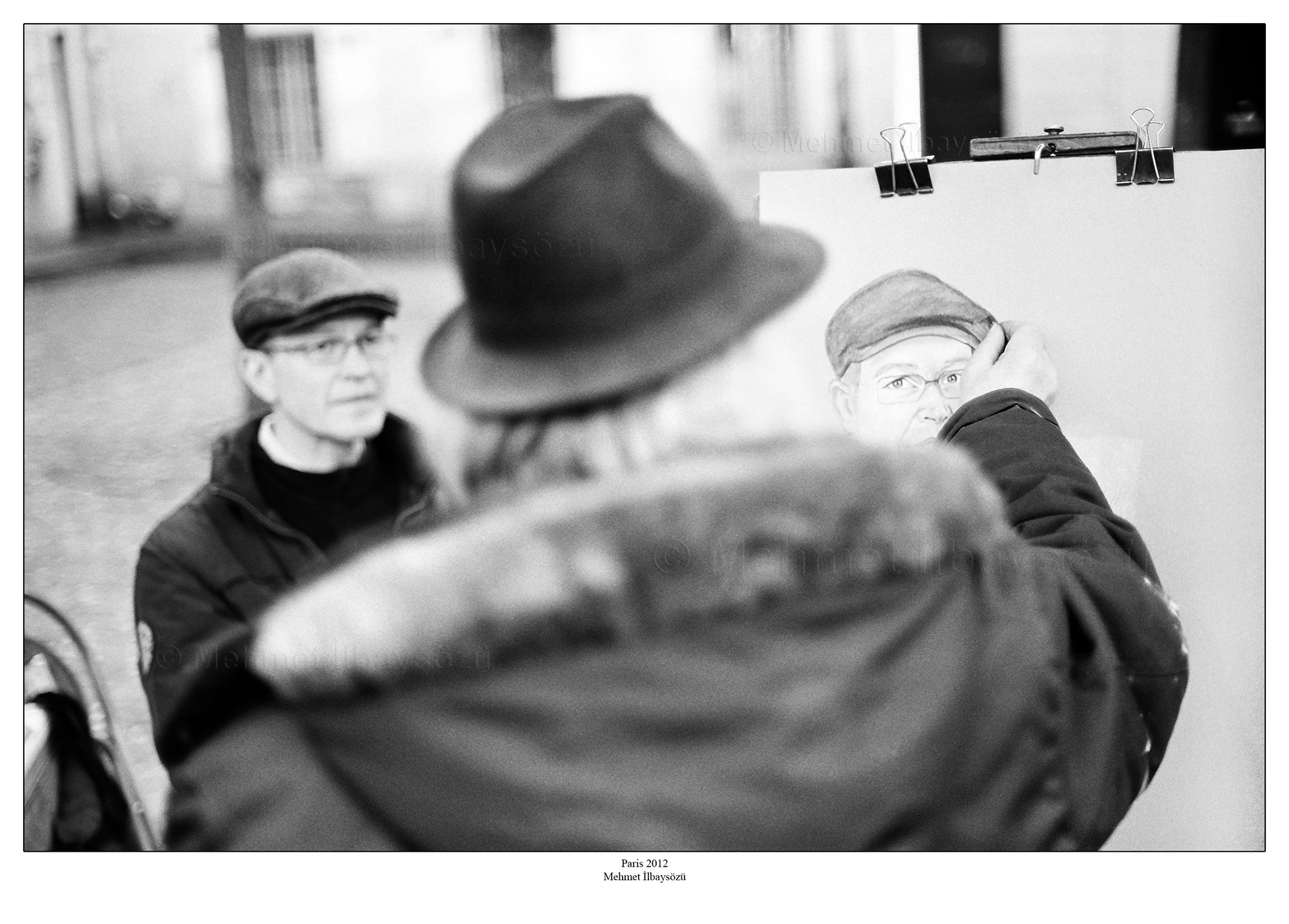

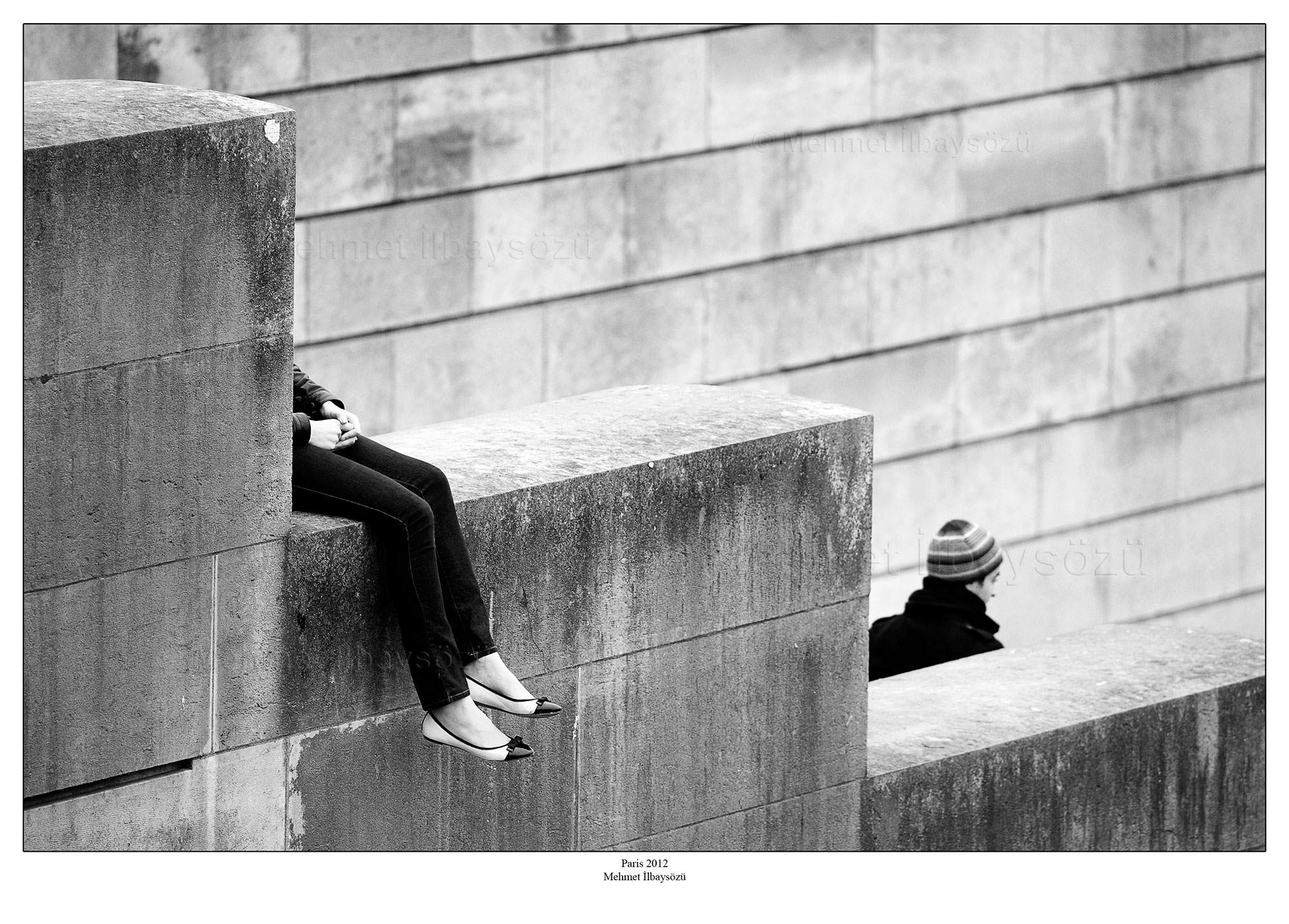

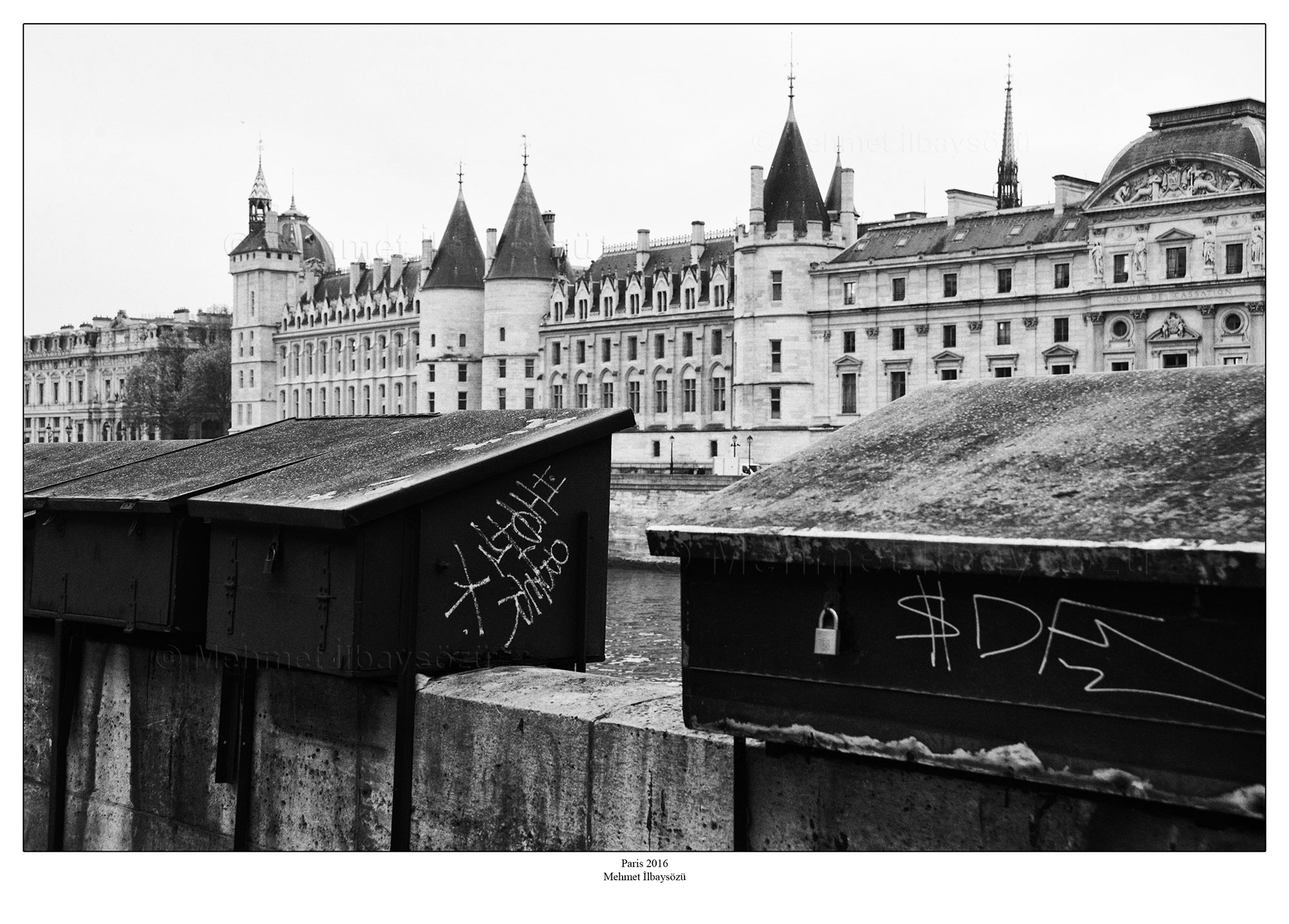

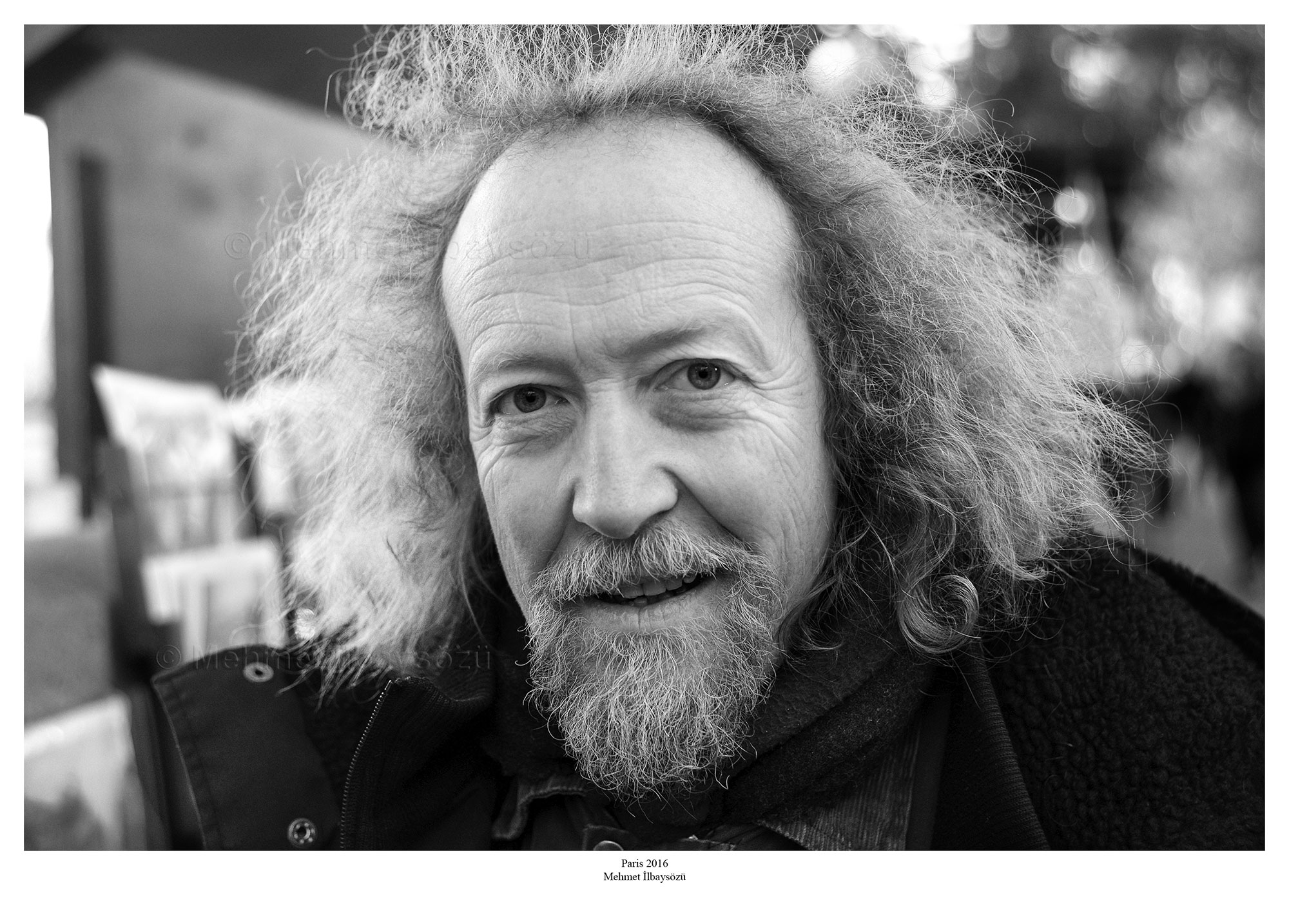

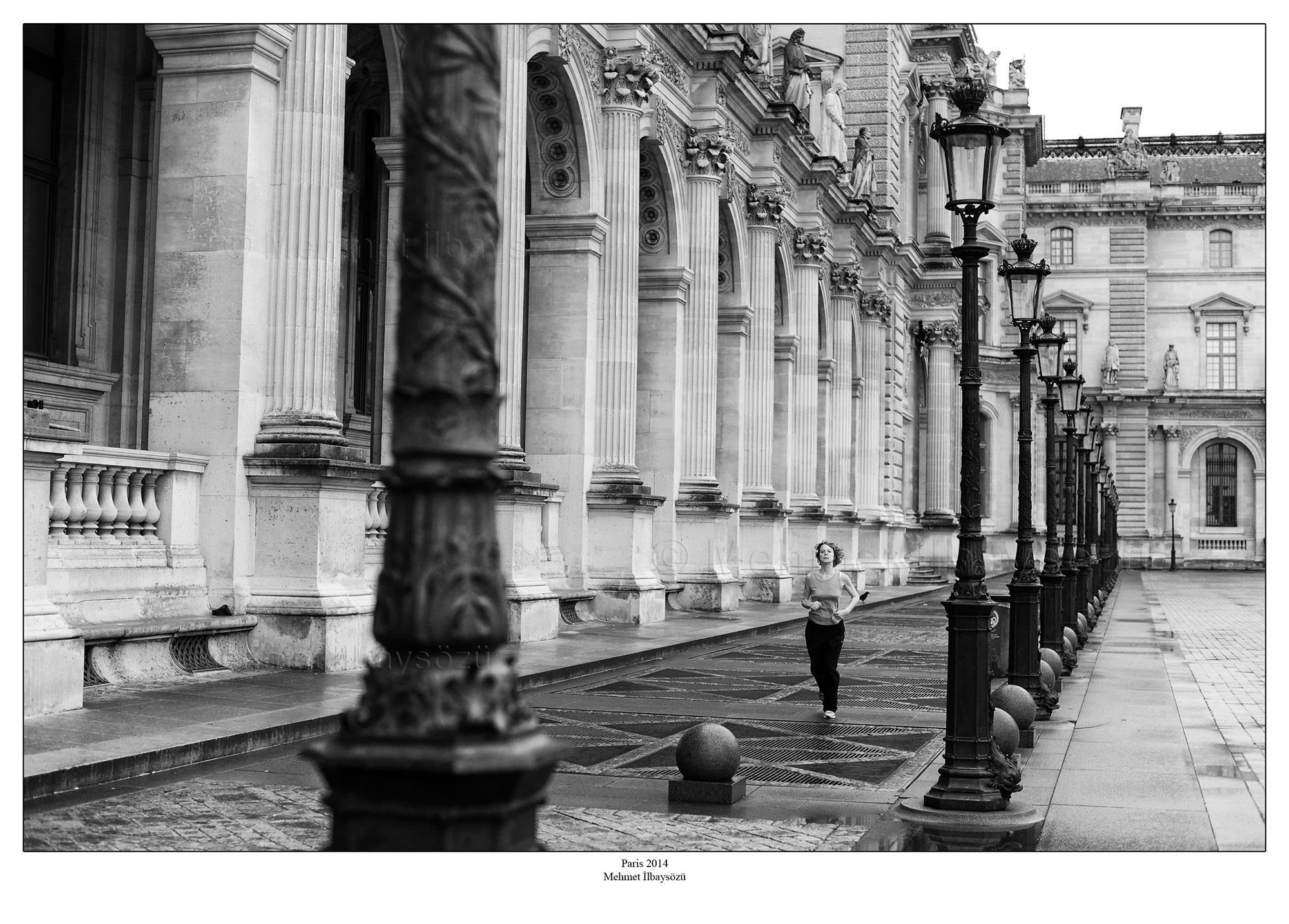

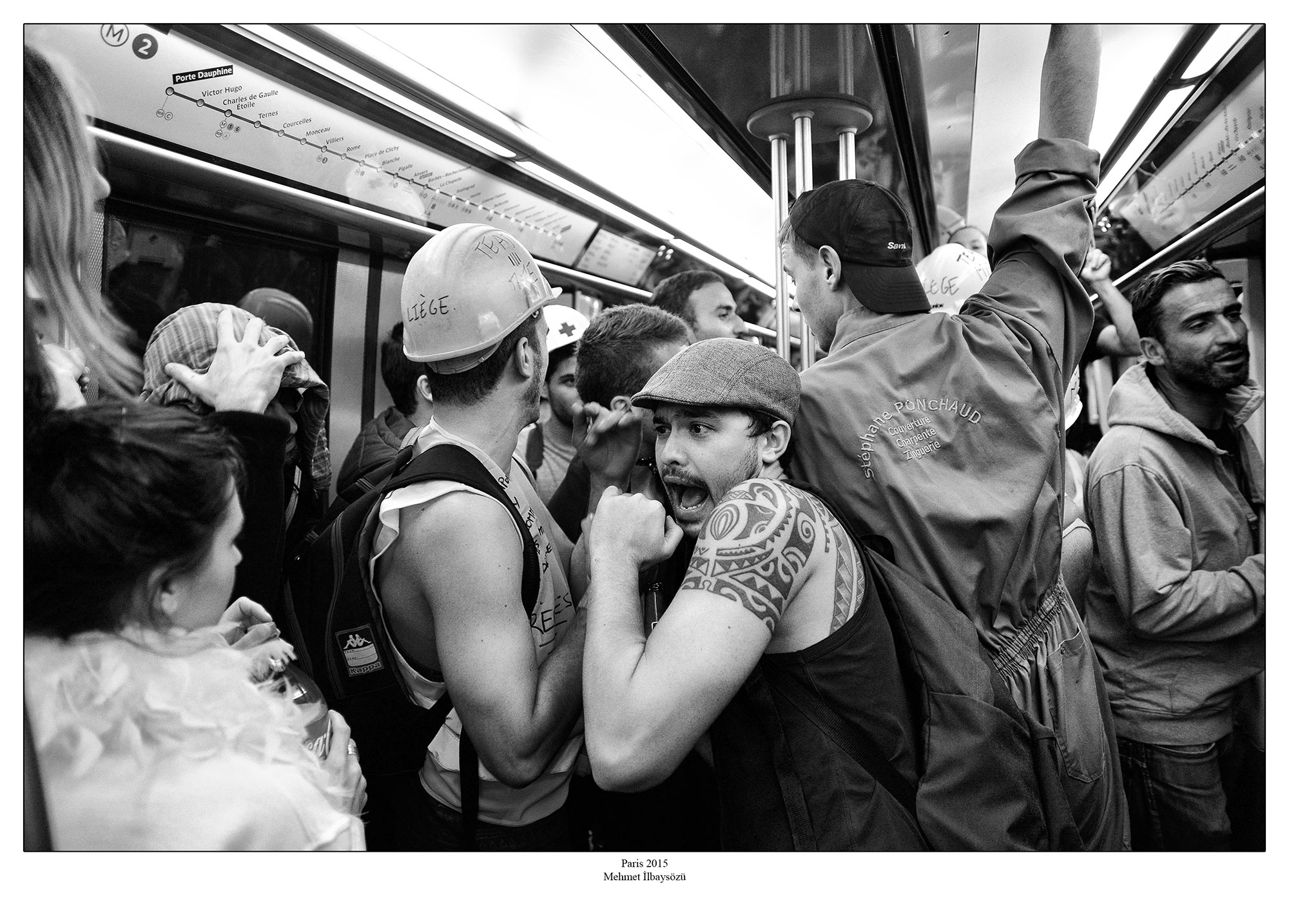

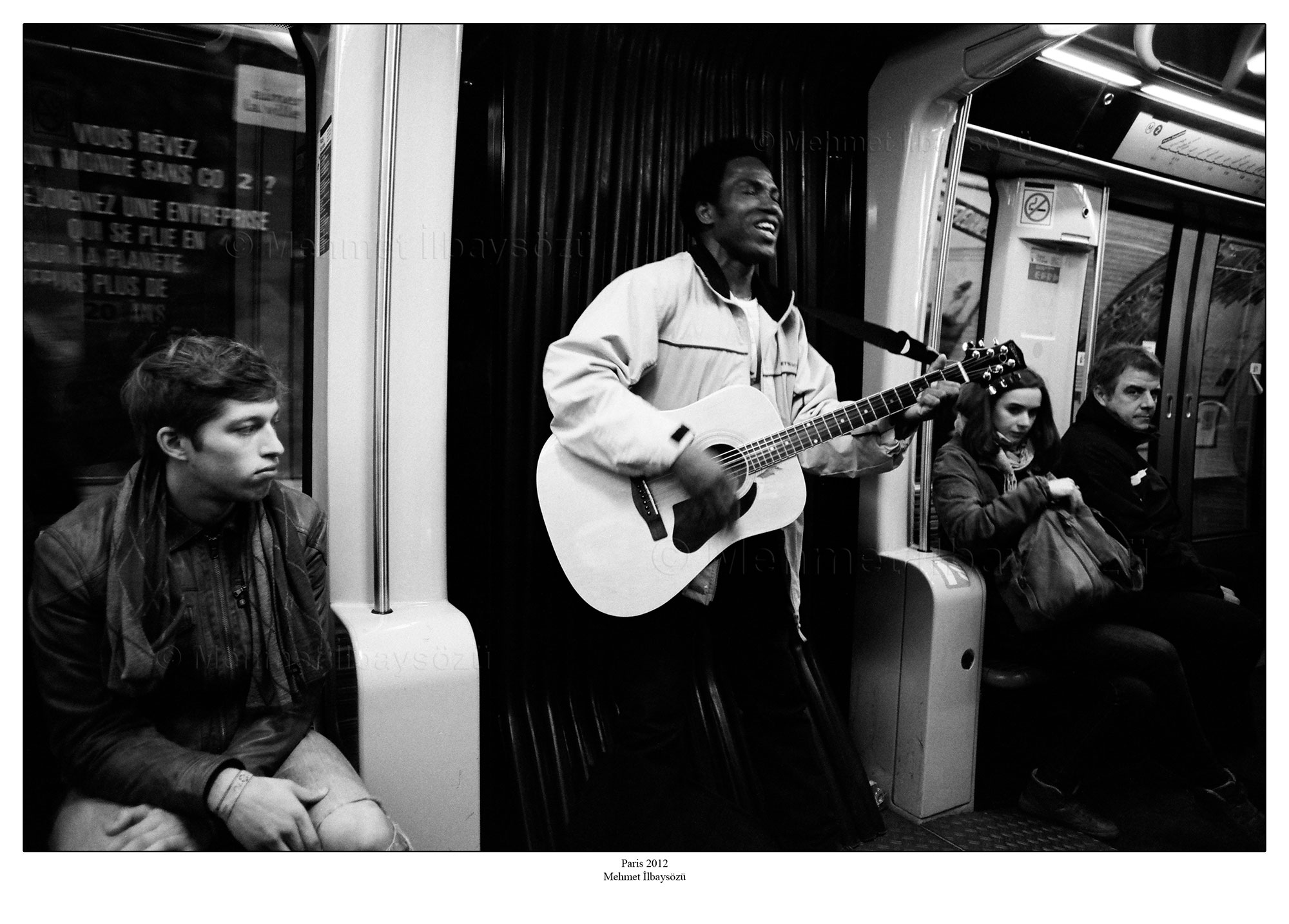

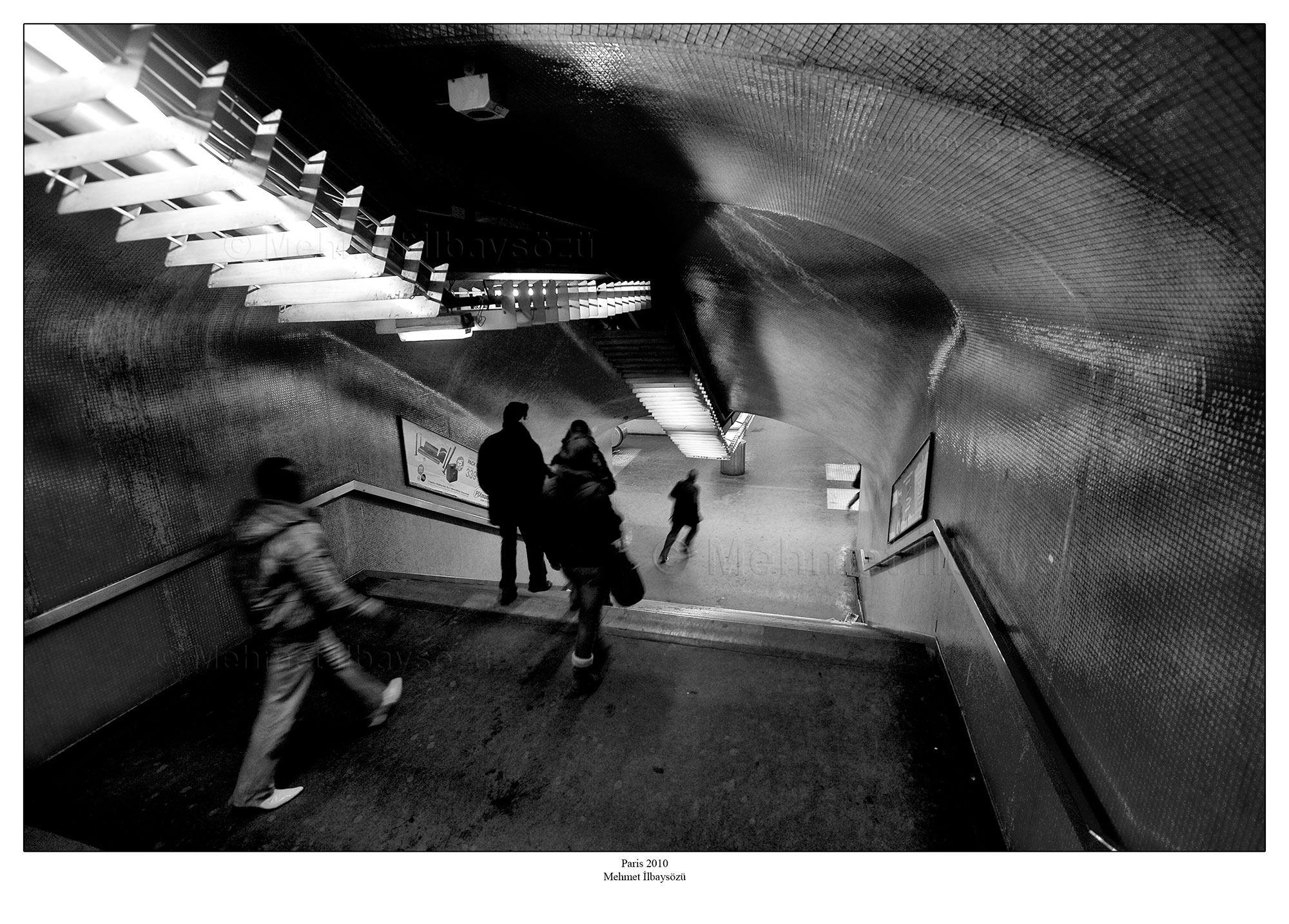

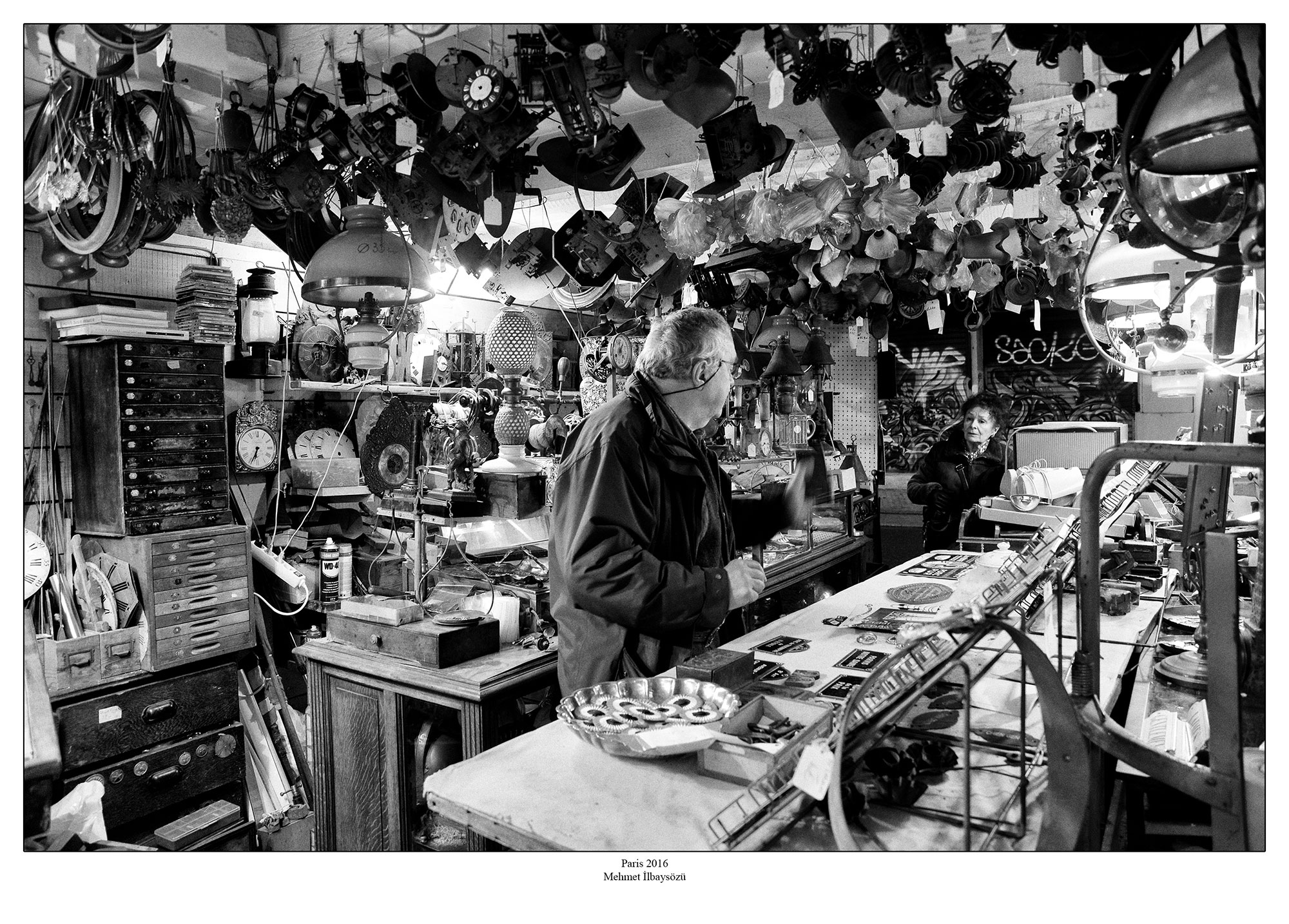

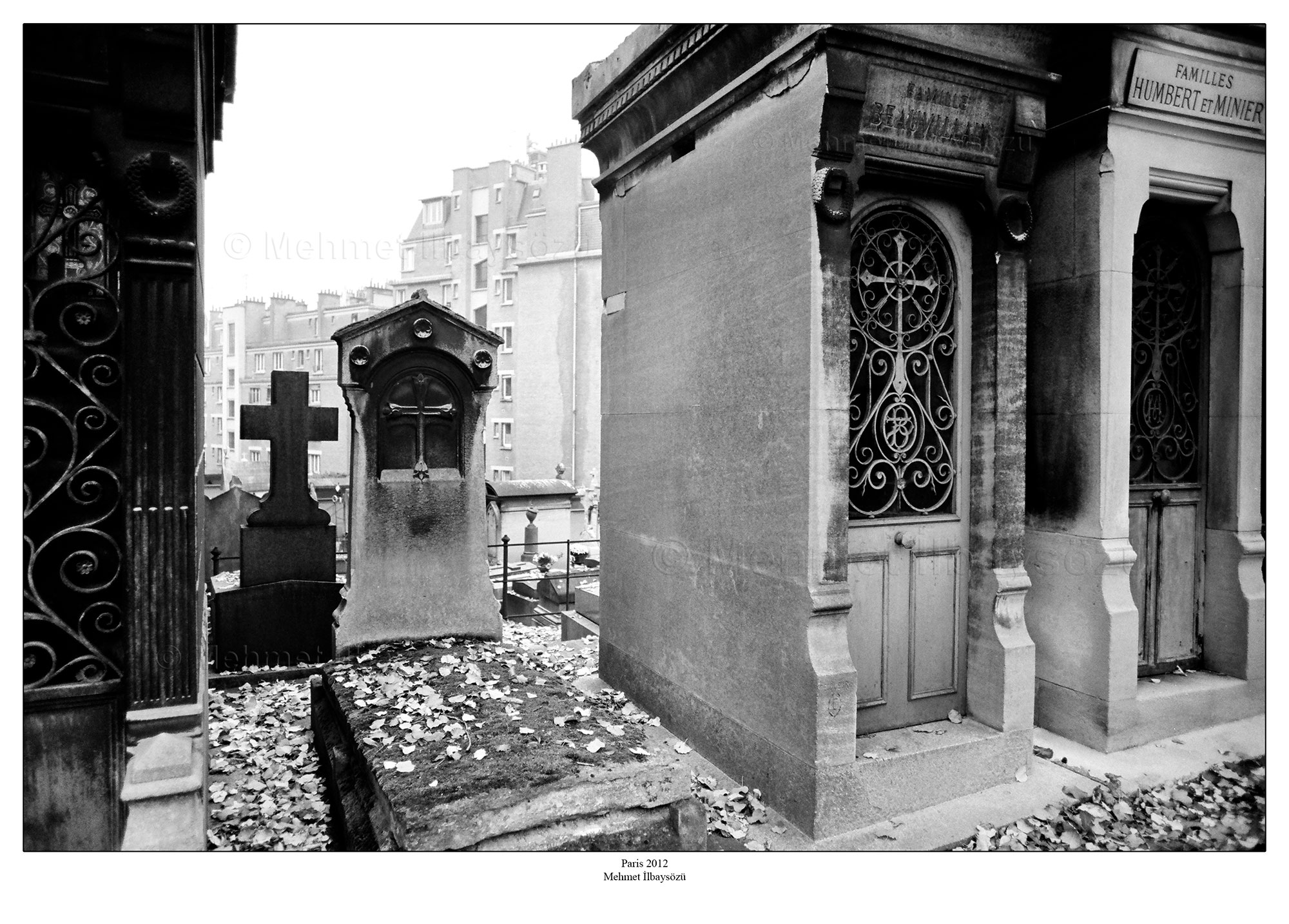

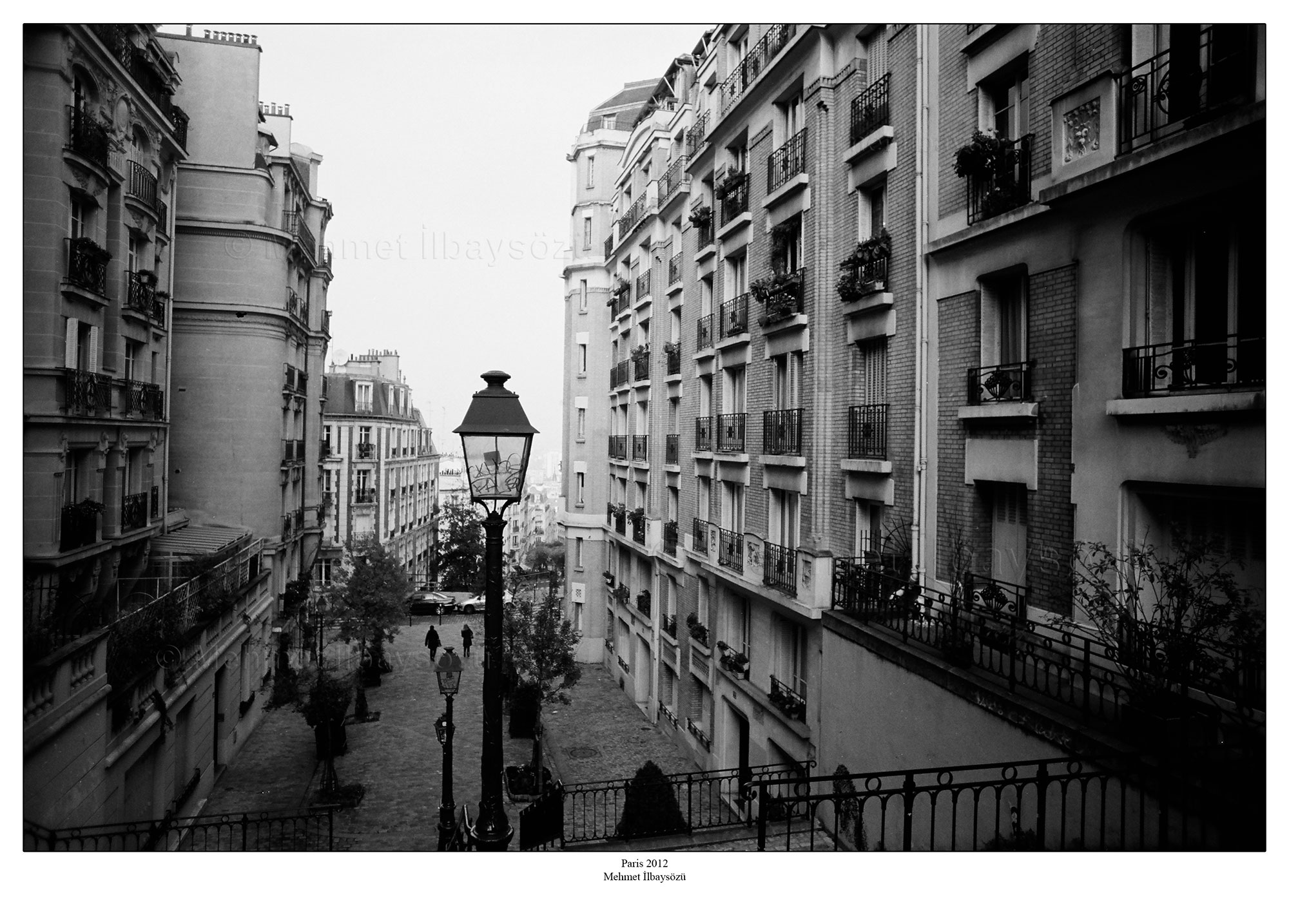

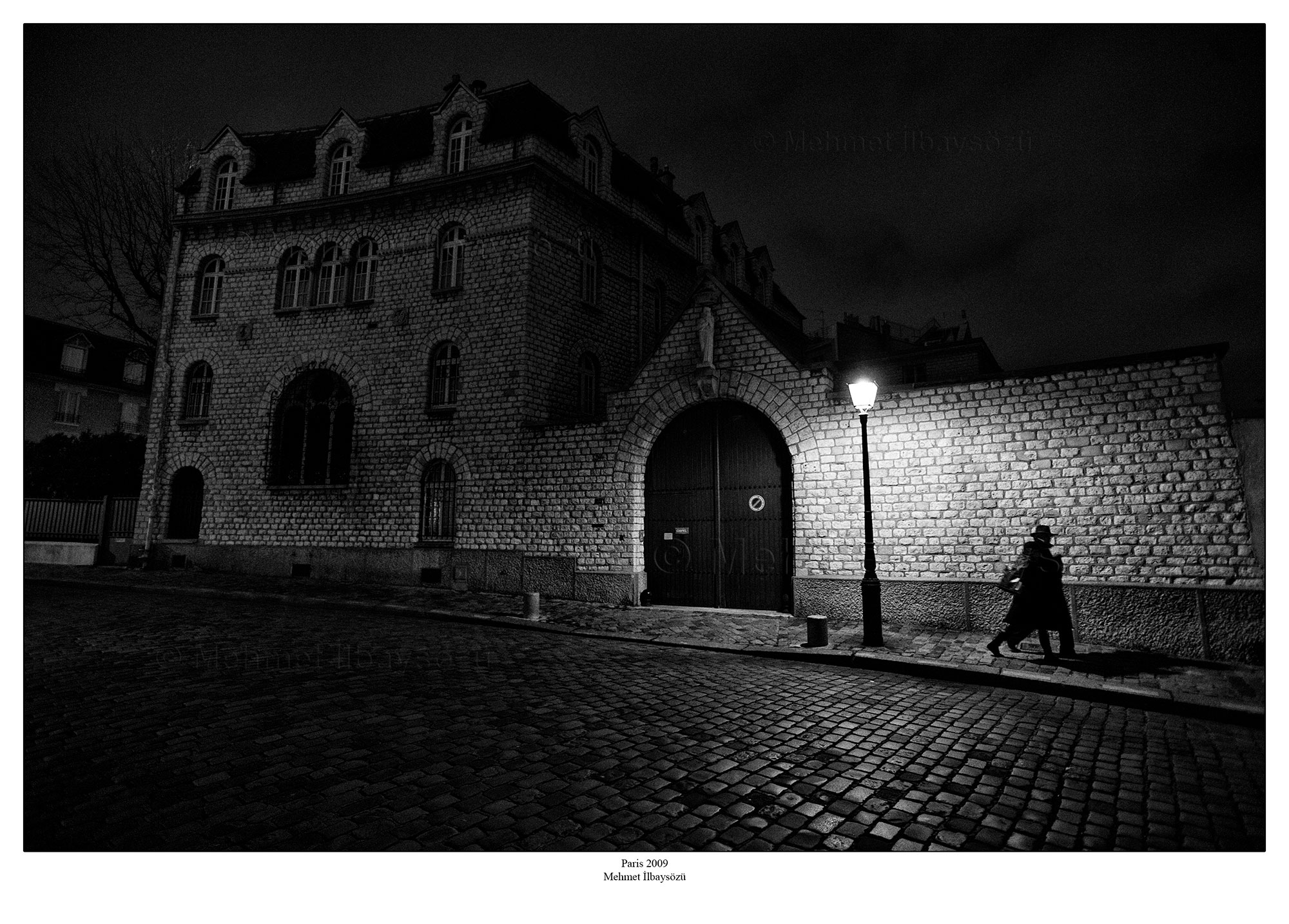

In Paris, the thing I do best is walk. And here, I share with you a few images from the thousands of moments I captured during those walks.

Presented to you:

Paris — my father’s legacy.

2009-2016 © Mehmet İlbaysözü

All rights reserved. Photographs and text may not be copied, reproduced or distributed without the written permission of the owner.